By Maddy Gordon, Spencer Bott and James McConchie

“In a 15 second video, they are required to show through dance or make moves or acts that represent how to be ‘not manly’ based on the social standards or social norms. This challenge has gone viral proven by the number of people who already watch the videos with hashtag #endtoxicmasculinity is 245.6 million in total”

In a globalised, social media connected world, the power and influence of content creators is demonstrated on platforms such as Tik Tok. The increasingly popular site takes everyday people and shoots them to stardom overnight. The platform has the power to showcase diverse representations of gender, sexuality and masculinity but does its algorithm allow this diversification to be seen and accepted?

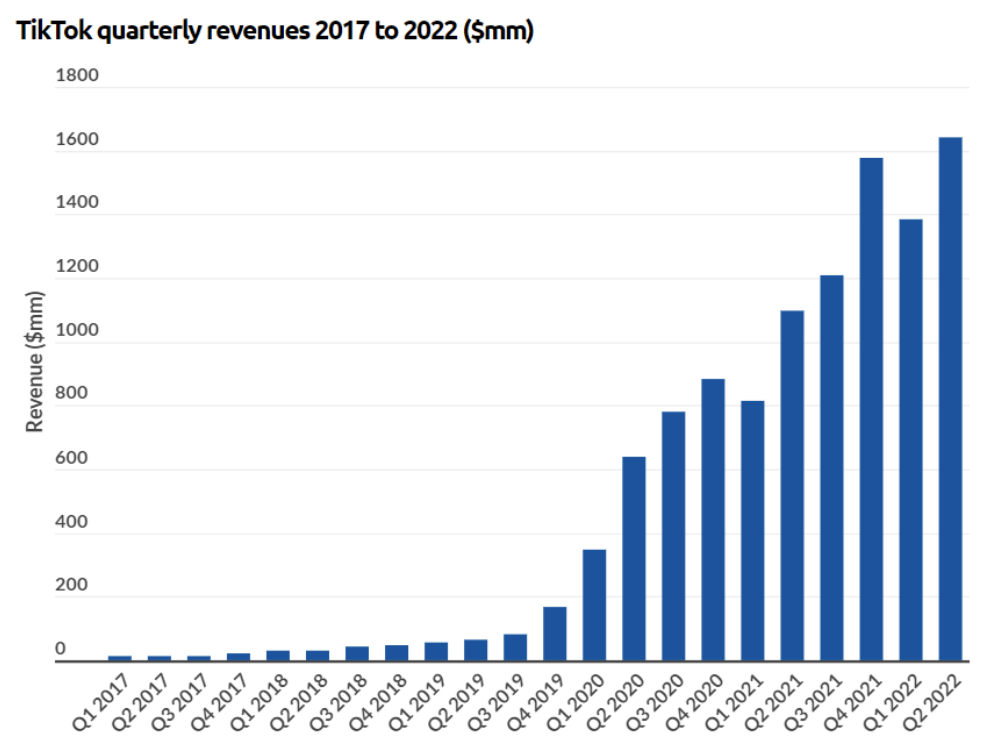

Tik Tok has had a large dose of overnight fame, taking the world by storm during the height of Covid-19 lockdowns, and now continuing into late 2022. It has over 1.4 billion monthly active users, positioning it as the fourth most popular social media app; only behind Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. The app has been downloaded 2.6 billion times already and has 138 million active users in the United States alone. Tik Tok strives to provide a sense of belonging, it engages communities of like minded people with opportunities to express one's identity and beliefs in creative ways.

This swift rise to fame is evidenced in the users of the app as well. Many recent articles comment on the ability for people, businesses, songs and dances to become ‘viral’ essentially overnight. Anyone has the ability to gain a large following and with a such a wide audience, the influence of some users on the app is incredibly far reaching.

When considering this power and influence it's important to contest the messages, discourse and themes that ‘trend’ on the platform. Subjects around identity, race, gender, religion and ethnicity become particularly relevant. When specifically considering representations of masculinity on the platform does Tik Tok provide a platform to celebrate diverse masculinity? Or does its algorithm allow for reproduction of hegemonic masculinity ideologies?

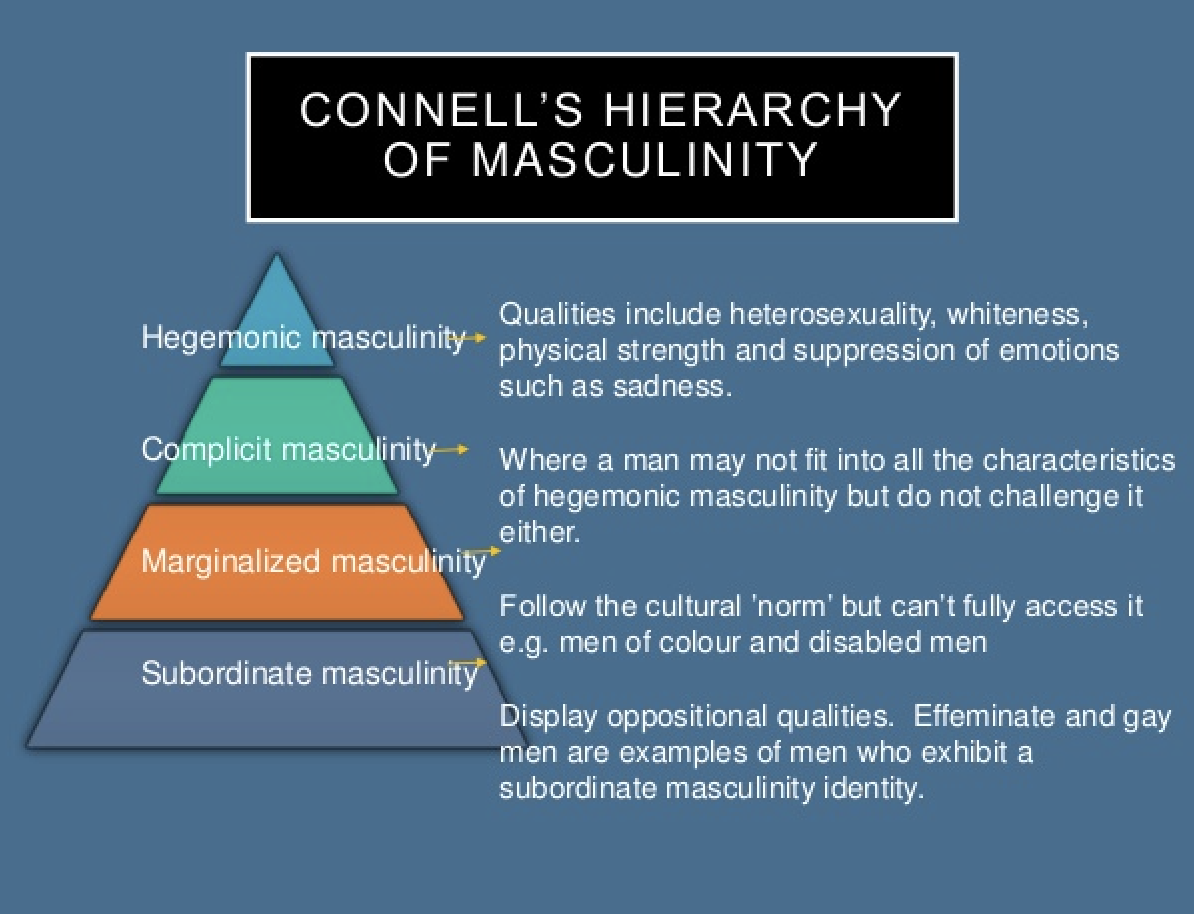

When considering different types of masculinity and how they can be represented, Raewyn Connell provides a hierarchy of masculinity that is a good outline to discuss. She details hegemonic, complicit, marginalised and subordinate masculinity as clear different distinctions.

Looking at this hierarchy and considering Tik Tok content and creators, it is interesting to determine how traditional structures outlined more accepted and less accepted representations of masculinity and how these are perhaps shifting. More recent studies start to examine social media, the accessibility of information and a notable transition towards more fluid, less rigid frameworks of masculinity. Tik Tok has become a platform to dispute linear representations of masculinity, the construction of gender norms and contest what is considered traditionally masculine. User generated content intertwines production and consumption, allowing more diverse representations but perhaps limiting them to certain audiences.

While considering Connell's hierarchy, rhetoric such as toxic masculinity often refers to the top of the hierarchy - hegemonic masculinity. Tik Tok provides many examples across a spectrum of masculinity representation that includes those who embody hegemonic (toxic) masculinity and those who embrace subordinate masculinity.

“The jumble of groups and philosophies that centre around ideas of toxic masculinity is commonly referred to as the "manosphere."

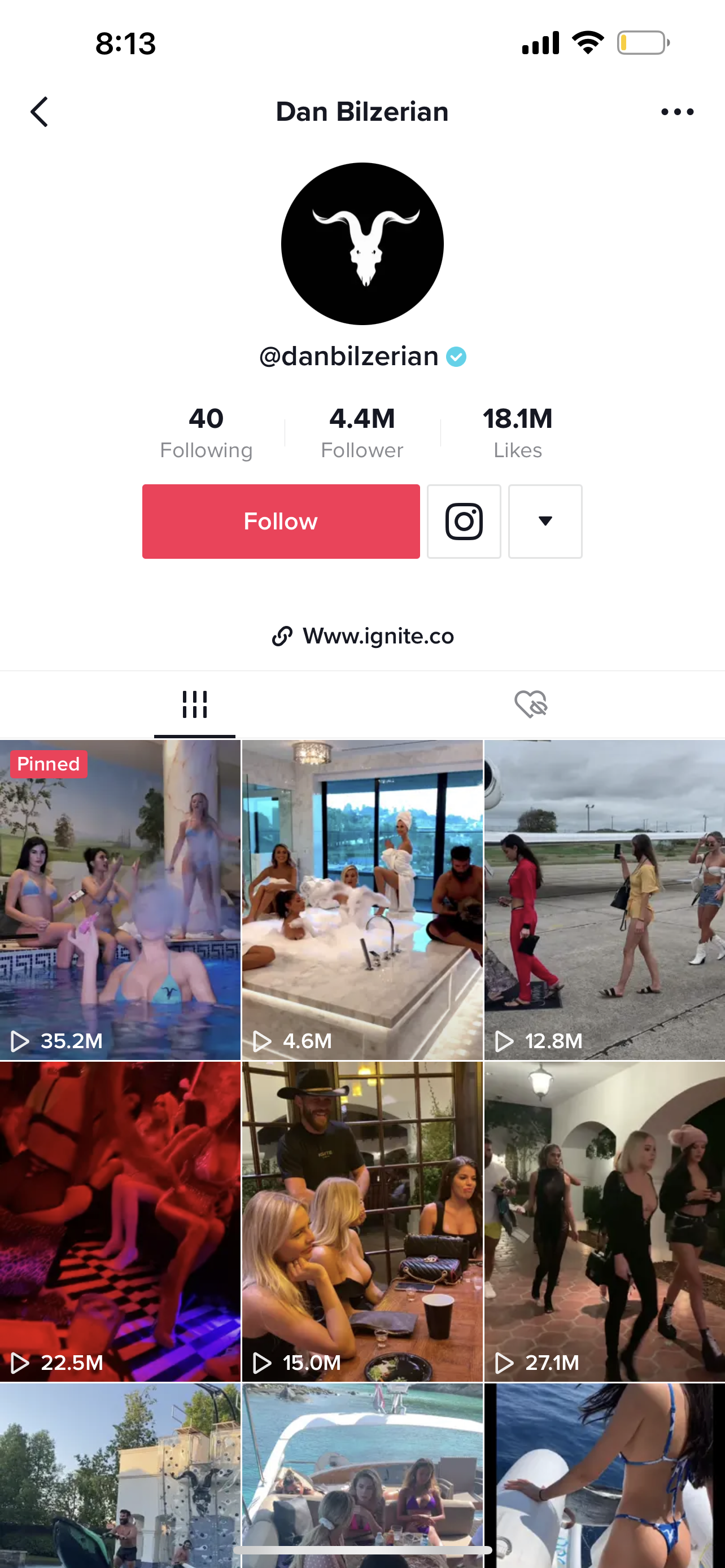

Some popular examples include users such as Andrew Tate, Dan Bilzerian and Jordan Peterson. These ‘celebrities’ target young, impressionable people, their content is often derogatory towards women and the LGBTQIA+ community as well as setting unrealistic body and idealised lifestyle expectations. Dan Bilzerian is always surrounded by large groups of bikini clad women. Andrew Tate preaches about owning women, claims mental health doesn’t exist and only weak men cry. While Jordan Peterson is rigid in beliefs around gender roles and men’s imperative to not be weak. They define and embody hegemonic masculinity centred around whiteness, heteronormativity, money and muscles.

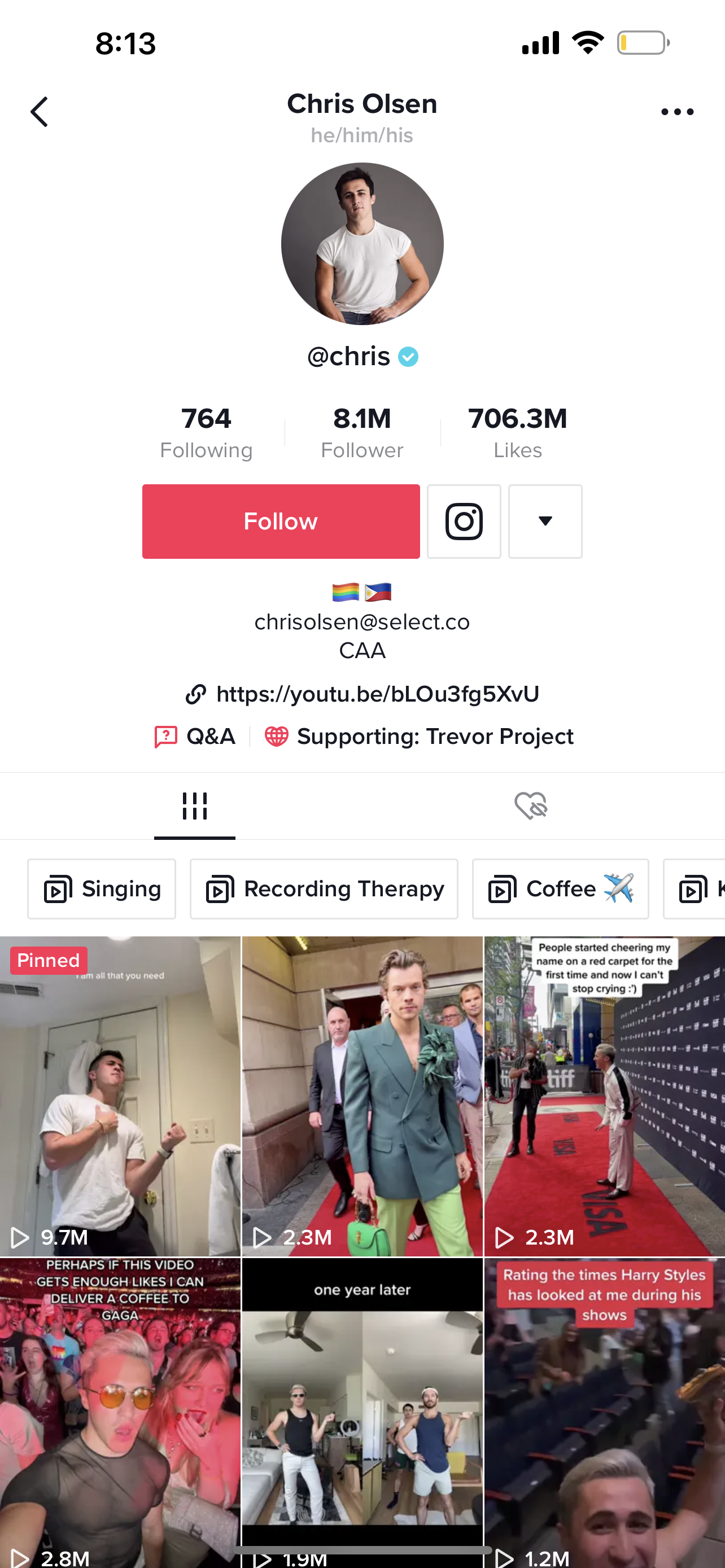

It’s interesting to then compare these users to those who embrace subordinate masculinity and whether the audience interaction, following, participation and power of voice varies. Some popular users include Michael Finch, James Charles and Chris Olsen.

They are all proud members of the LGBTQIA+ community and many comment they wouldn’t have the confidence to express themselves in their masculinity how they do if they didn't have Tik Tok. Chris Olsen is openly gay and considered quite feminine, he often records meetings with his therapist and is honest and upfront about his emotions on his platform to his followers; breaking down stigma and stereotypes around men’s mental health. These stars, plus many more have considerably more followers and engagement than those who embody hegemonic masculinity.

It’s important to note that there are also many examples that blur the distinctions between the categories – creators that through the use of music, language, clothing, dances and other trends showcase different representations. It’s in the way that Tik Tok content can challenge traditional forms and structures of masculinity and suggests linear categorisation can no longer occur.

“Some masculinity experts have pointed out that when these creators push the boundaries of gender expression, they signal permission for other boys to be authentic and expressive about gender."

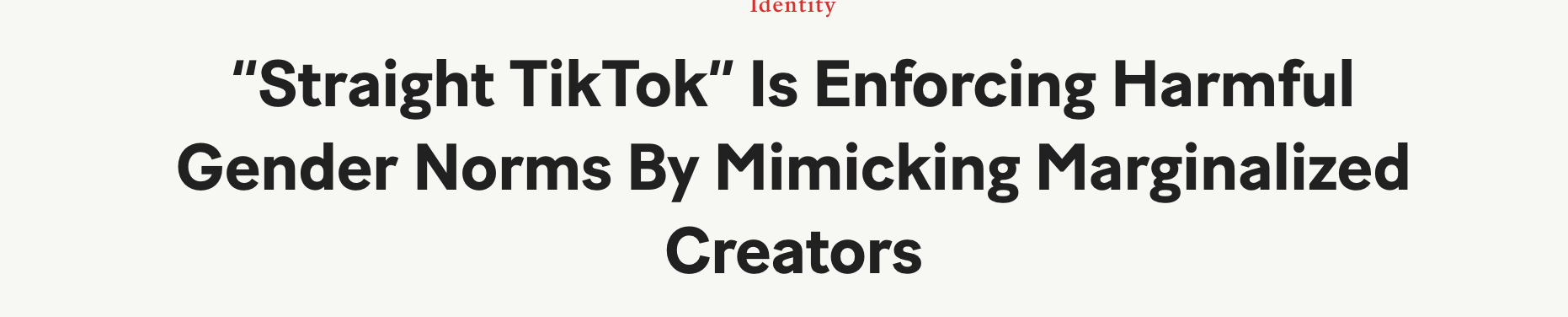

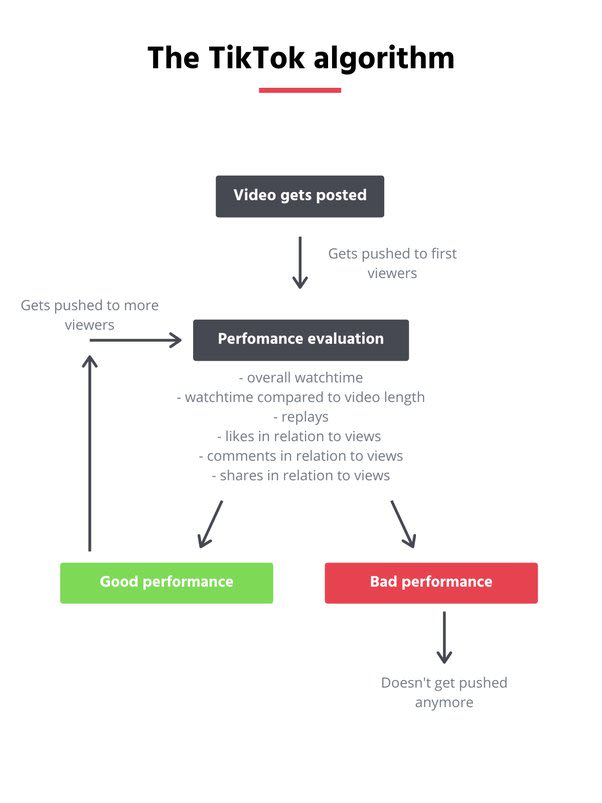

While recognising this ability of expression and representation, it's important to note the structure of Tik Tok and how this may limit the diversity people see. Like many other social media sites, Tik Tok tracks activity and through an algorithm, curates a content feed personalised to each user. People refer to being 'on a side of Tik Tok' where their videos often have association to one another as well as the users interests, and consumption patterns.

This means that while diverse representations of masculinity may be uploaded, it may not be available to all viewers. Within echo chambers, content is left out and users are restricted to linear masculinity representations. Those who engage with Andrew Tate, continue to see Andrew Tate, Dan Bilzerian and Jordan Peterson.

But are times changing....

There is increasingly more diversity and masculinity representation that is being accepted and embraced across social media sites such as Tik Tok. Those who embody subordinate masculinity have large followings and strong influence, supporting fluid expressions of identity, sexuality and masculinity. The global accessibility and interconnection social media provides compresses global issues and ideologies into small 10-30 second clips. While echo chambers create curated feeds and limit access to certain media, there is no denying more diverse representations are beginning to shine through.

References

Connell, R. W. (1998). Masculinities and globalization. Men and masculinities, 1(1), 3-23.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27640853

Das, S. (2022, August 6). Inside the violent, misogynistic world of tiktok’s new star, andrew tate. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/06/andrew-tate-violent-misogynistic-world-of-tiktok-new-star

Kalter, L. (n.d.). TikTok Creators Are Destigmatizing Men’s Mental Health. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from WebMD website:

https://www.webmd.com/men/news/20210824/tik-tok-creators-destigmatizing-mens-mental-health

Karagiannis, E. (2021, April 1). Harry Styles Defeating Toxic Masculinity and Leaving His Stigma in the Fashion Industry - L’Officiel. Retrieved from www.lofficiel.cy website:

Liver King: The Untold Truth. (n.d.). Retrieved from Garage Strength website: https://www.garagestrength.com/blogs/news/liver-king

.

Lightning, T. (2021). Examining attitudes toward gender outlaws on Tik Tok.

Puzio, A. (n.d.). Straight Boys Pretending to Kiss on TikTok Isn’t the Gender Revolution

Some Think It Is. Retrieved from Teen Vogue website:

https://www.teenvogue.com/story/straight-tiktok-gender-norms

Willingham, A. J. (2022, September 8). Misogynistic influencers are trending right now. Defusing their message is a complex task. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from CNN website: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/09/08/us/andrew-tate-manosphere-misogyny-solutions-cec/index.html

Zhafirah, Faizzah. (2021). Sassy Challenge on Tiktok as A Campaign to End Toxic Masculinity.

10 Reasons Why Dan Bilzerian is Everything Wrong with Society – FEM Newsmagazine. (n.d.). Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://femmagazine.com/10-reasons-why-dan-bilzerian-is-everything-wrong-with-society/