Masculinity, Incels, and Radicalisation on Social Media

Conversations about male radicalisation, misogyny and the ‘incel’ ideology have made their way into the mainstream in recent years, thanks to social media. People have become more educated on these concepts and the issues that come with them, as more often than not, they are associated with violent crimes against women- something we have seen an increase in over the past few years.

The rise of online platforms radicalising young men and feeding off their internalised misogyny is just the tip of the iceberg of the ‘manosphere’. Attacks on women, such as the recent stabbing in Bondi reveal more about the consequences of the harmful‘incel’ ideology. Toxic masculinity has always been an issue that people are more recently beginning to see the ramifications of due to exposure on social media.

As a society, it's important to not only validate the women who are victims of this issue but also be able to take a step back and see the bigger picture to strategise ways in which to combat these issues- starting at the source.

This story explores the rise in male radicalisation on social media, the violent ramifications of believing in the manosphere, and proposals for moving forward.

Content forecast: discussions of violence against women and men, radical ideologies, school shootings, mention of self-harm and harm to others.

What is the manosphere?

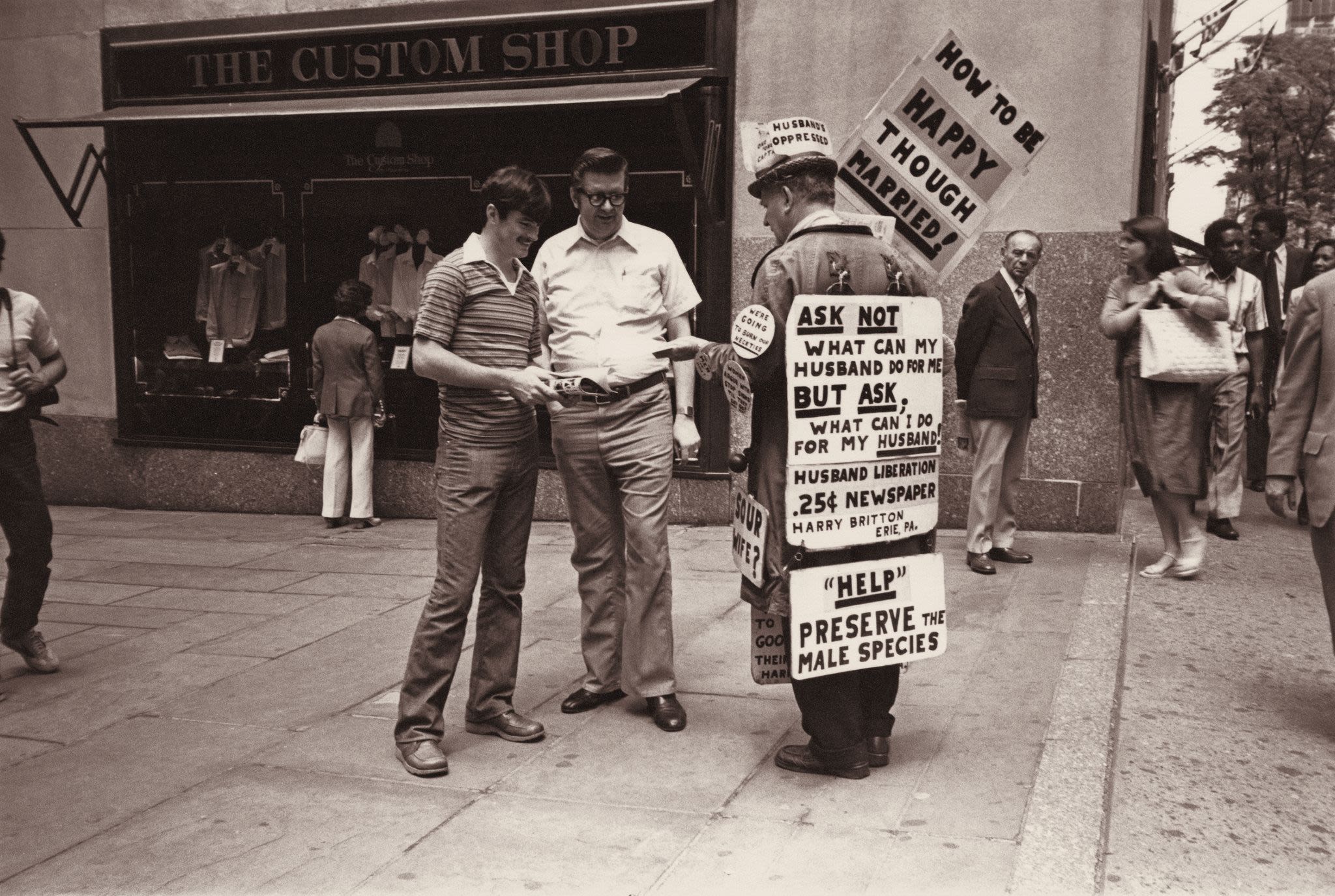

The manosphere is a collection of online men’s groups, such as Men’s Rights Activists, Men Going Their Own Way, Pick Up Artists, Incels (involuntary celibates), and Fathers for Justice. The Men’s Rights Movement can be traced back to the 1970s, when it emerged in opposition to the Women’s Liberation Movement as cisgender white men started to worry about their perceived diminishing social status due to the advancements of feminism. These groups mainly operated outside the mainstream, but in recent years specific alt-right commentators have popularised the movements. Think Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, and Andrew Tate. They all seem to empathise with men’s loneliness and pain while also capitalising on it in an era of confusion about feminism and LGBTQ+ progress. Part of their tactic is redirecting blame for the struggles of society onto a tangible enemy, which is in this case women, instead of fighting to change the systems of oppression.

Incels aspire to hegemonic forms of masculinity while simultaneously acknowledging their failure to meet the standards. They blame this failure on their perceived physical or mental deficiencies and women’s ‘selfish’ sexual motives and hypergamy. Radicalisation into these incel communities is also known as ‘taking the red pill’ to escape the matrix of society. Researchers write that “red pillers awaken to the “truth” that socially, economically and sexually, men are at the whims of women’s (and feminists’) power and desire. Radicalisation and the ‘redpilling’ of men online has become a pandemic.

Who is driving online misogyny and how quickly are boys getting radicalised on social media platforms?

A number of influencers have gained popularity in recent years, bringing the somewhat hidden ‘incel’ corner of the internet into the mainstream.

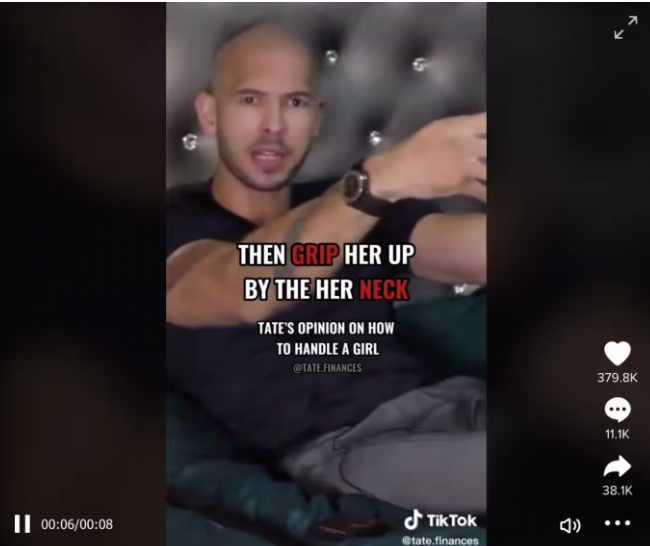

Andrew Tate is one of the most recognisable figures, a ‘manfluencer’ best known for promoting misogynistic and antifeminist ideology with a ‘playboy’ attitude. His content tends to target young boys around the age of 16 to 18. Tate offers his mostly male fans a way to make money, pull girls, and escape the matrix. He adopts a neoliberal lens that “applies market-based logic to various aspects of life, including social relationships” (Bujdei-Tebeica, 2023); this is evident in the way he speaks about dating as transactional and promotes ‘hustle culture’. After being arrested on human trafficking charges in Romania in 2022, parents, teachers and experts have become increasingly concerned about young boys’ involvement in Tate’s online ultra-macho world. They suggest that his views are fueling a rise in misogynistic attitudes.

Even though his social media accounts have been banned on most platforms, Tate’s ideology is still a widely discussed topic. Researchers from Dublin City University have found that “shutting down influencers’ accounts does not necessarily remove their content”, as social media platforms still allow reposted videos of his to circulate.

The heart and soul of Tate’s empire is an online ‘university’ that sells itself as “the world’s most advanced financial education platform”, called Hustlers University.

Screengrab from Tate's Hustler's University website

Screengrab from Tate's Hustler's University website

The platform is promoted with binary language of winners and losers, laziness and action, ‘brokies’ and hustlers to pressure men into joining so that they can ‘escape the matrix’. Unsurprisingly, his tactics are extremely misogynistic and hateful, and prey on young men's deep-rooted insecurities.

Mahmoud, a 25-year-old student from Cairo, Egypt was one of the hundreds of thousands of young men across the globe who considered themselves diehard Tate fans, inhaling his misogynistic, egotistical, hyper-capitalist ideology daily. Mahmoud found himself completely infatuated with Tate’s worldview not long after signing up to Hustlers University. Isolated from his friends and family, he would spend up to 12 hours a day on the platform, convinced he would become rich by following Tate’s advice. Convinced of Tate’s innocence despite the human trafficking charges he faced in Romania, Mahmoud, like many others, was willing to ‘fight’ to defend Tate. It just goes to show the radicalisation of these boys at present.

According to the UK’s Head of National Counter-Terrorism, statistics have grown recently showing a worrying rise in the number of suspected incels being referred to the Prevent Counter-Terrorism scheme. Police have also stated that although the movement is “not currently considered a terrorist ideology”, it “has the ability to inflict horrible acts of violence”.

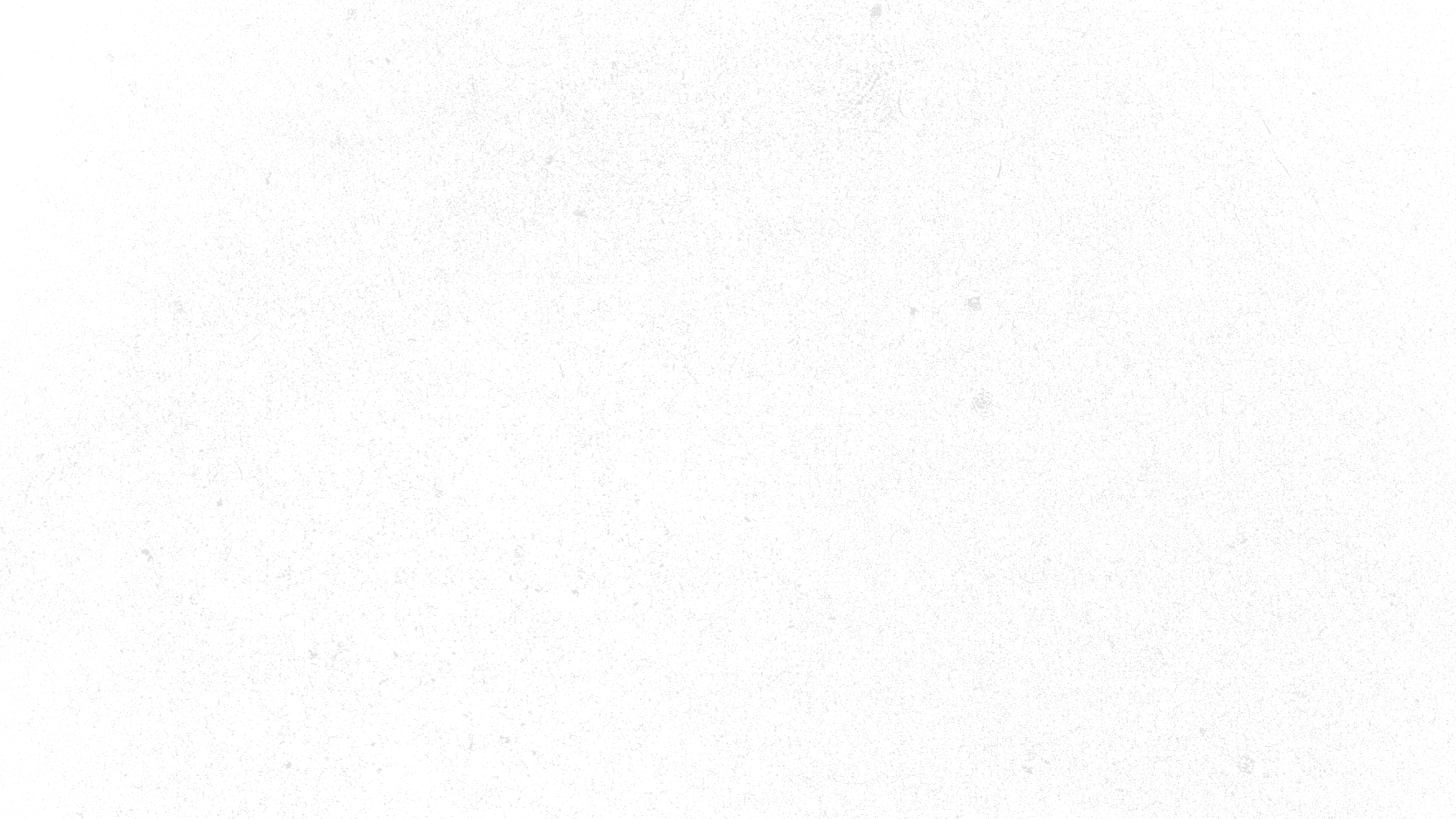

A study done by Dublin City University using ‘blank’ male-identified accounts on YouTube Shorts and TikTok found that within 23 minutes of signing up, accounts were bombarded with “masculinist, anti-feminist and other extremist content” whether they sought it out or not. A similar study conducted by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue concluded that the “avatar accounts of young boys and men were algorithmically recommended content with overt misogynist and ‘manosphere’ messages”.

Image from ISD study Algorithims as a Weapon Against Women

Image from ISD study Algorithims as a Weapon Against Women

Videos promoting hateful views on women’s rights and commentators like Jordan Peterson, Andrew Tate, and Ben Shapiro were recommended to all accounts.

While the study done by the ISD did not outline the connection between platforms pushing Manosphere content and young men committing acts of violence, the researchers raised serious concerns about the unregulated algorithms and the fact that the content appears to target young male viewers. “Even if the content does not lead to radicalisation, it encourages a dehumanising, disrespectful attitude towards women, and is delivered in deluge without opposing perspectives or any semblance of balance that could represent a dialogue or debate”.

Ultimately, much more work must be done to regulate algorithms, set age limits and expand the definition of ‘online harm’ to address gender-based violence (Thomas and Balint, 2022).

Understanding radicalisation and male violence in the wider societal context

The recent Bondi Junction Stabbing has been seen by many as an act of misogynistic violence. The killer, identified as Joel Cauchi, stabbed 17 people, 14 of whom were women. Reports from the mall say that he was deliberately targeting women. Cauchi's father told reporters that his son could have done this out of frustration at his inability to date women. These frustrations are not unique, they are part of what is known as the incel ideology. Incels are "heterosexual men who blame women and society for their lack of romantic success". There is deep-rooted anger towards women for denying them sex, as well as intense self-loathing, which externalises as outward displays of violence. Experts say that misogyny-motivated terrorism is a rising threat all over the world, and this is just one example.

Cauchi had been diagnosed with schizophrenia at 17, and his parents note that he had gone off his medication around the time of the stabbing, with agreement from his doctor. His parents suspect that psychosis and deteriorating mental health played a large role in the stabbing. However, experts warn that this cannot be viewed as an individual issue, or only due to mental health. Josh Roose says that "you can be mentally ill and still cognisant and capable of holding a set of beliefs". Roose warns against suggesting that people with mental illnesses are incapable of holding a set of values or demonstrating any agency.

Many violent male crimes are excused by attributing their actions to mental health issues. This may be part of the issue, but it is vital to understand the context of widespread gendered violence as part of an ongoing crisis of masculinity.

It can be easy to individualise the issue of male violence or look at news headlines as extreme outliers. But the fact is, violence is an accepted part of masculinity in society, it is not unusual or unexpected. The media normalises and praises male violence and dominance onscreen, teaching boys how to behave from an early age. In Jackson Katz’s documentary, he links the changing representations of the size of men's bodies in children's toys and media, to a greater emphasis on size, strength and muscularity; men are taking up more symbolic space in an era when women have been challenging male power.

Katz, J. (1999). Tough Guise: Violence, Media, & the Crisis in Masculinity https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24Tbw9_eL_U

Katz, J. (1999). Tough Guise: Violence, Media, & the Crisis in Masculinity https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24Tbw9_eL_U

At all stages of life, boys and men are bombarded with images of masculinity that put a lot of pressure on them to conform. The effect of this narrow and destructive way to be masculine is vast and often materialises as men harming women and other men. “Engaging in violence is a sword as well as a shield; it is both a way of defending oneself against shame and a way to affirmatively demonstrate one’s manhood”(Harris 2011, p. 26). Therefore, men participate in violence to prove their masculinity.

Where do incels and male radicals fit in here? Well, Katz uses the Columbine School Shooting as an example of young men who didn’t fit into the tough, muscular norm of masculinity; they were outsiders, bullied by the jock culture of hegemonic masculinity. Katz argues that they could find ‘equal footing’ by using guns to harm and kill others, gaining a “grotesque form of respect”. Many incels who commit violent crimes are also ostracised from society and angry at the unrealistic expectations imposed upon them. The very fact that there is a surge in male radicalisation and incel ideology shows that there is a crisis in masculinity. The crisis is not in the alt-right, conservative fear that men are ‘no longer men’, but rather in the sense that men cannot live up to the masculine norms we have as a society, and are cracking under pressure with no way to express themselves other than how they have been taught since birth: violence.

Rethinking Masculinity: Where can we go from here?

Where to from here? As a society, we must devise a strategy to target misogyny and hate directly. Shannon Zimmerman argues that “we need to consider much more upstream things like understanding toxic masculinity and where misogyny comes from”. There are already examples of this in the community. One of these is the Talking Masculinities Project which has been going into schools around New Zealand, informing and educating staff on messages pupils may receive on social media that could lead them into misogynistic attitudes.

https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/misogynistic-attitudes-tackled

https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/misogynistic-attitudes-tackled

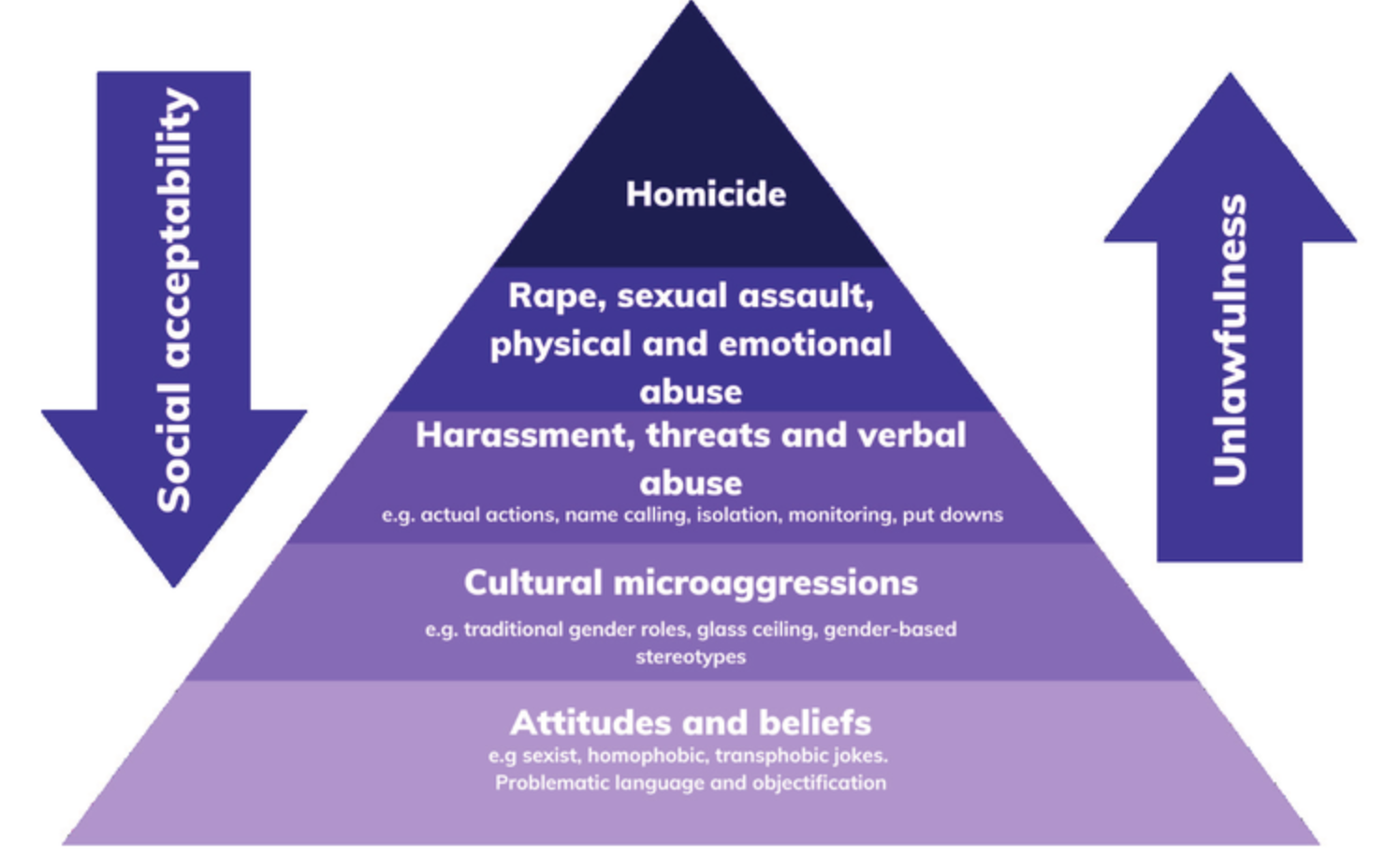

The project has been very informative to teachers in Dunedin schools, Dr Kris Taylor says it is about “giving them [staff] some tools to recognise when boys are saying some things that they may not have understood before". The workshop describes a ‘violence pyramid’ which illustrates the escalation of violence that boys may succumb to once exposed to online messaging.

It addresses other potentially harmful behaviours brought on by online messages such as racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia. The violence pyramid shows how some of the more accepted or seemingly harmless beliefs or attitudes that many young boys hold are part of a much larger issue.

Additionally, we must embrace men by understanding the appeal of the manosphere to those in it. Empathy, tolerance and patience must be used to lead men away from these corners of the internet and make them feel connected with wider society. Youth mentorship programs with a positive male role model may be helpful to re-integrate boys into communities. Better mental health support is also crucial with a focus on developing a stronger sense of sense and alleviating loneliness, as incel ideology and manfluencers often prey on feelings of isolation, loneliness and low self-worth. In ‘Feminism is for Everybody’, bell hooks emphasises this point, saying that if we educate men about what feminism truly is, “they would no longer fear it, for they would find in the feminist movement the hope of their own release from the bondage of patriarchy” (hooks 2000, p.9). Men who actively engage in patriarchy and hegemonic masculinity are unhappy; these modes of domination require constant adherence to impossible masculine norms. Even more unhappy are the incels and redpillers who are further ostracised from society, glaringly aware of their failure to live up to the narrow expectations of hegemonic masculinity. With the help of feminism, men can also free themselves from patriarchy and live a happier, fuller and more inclusive life.

Society must be re-educated with the support of families, schools, communities and policymakers working together. One way policymakers can make a difference is by thoroughly checking users’ ages and enforcing stronger regulations of social media algorithms. Managing harm on social media could even mean changing the current system and rethinking much of the current legislation.

- Raise and enforce age limits of users on social media by requiring a form of valid ID to be provided when signing up to verify the user’s age. Social media platforms must ensure age-appropriate content is shown to underage users and parental supervision should be encouraged to allow open discussions about what is seen online.

- Media companies must be held accountable for regulating the content on their platforms. Companies must devise strategies to limit harmful exposure to online content and stop prioritising profit over safety. In the ISD study, it was recommended that algorithms must be targeted and regulated as they are human-designed pieces of code that recommend misogynistic content to young boys and men.

- A shift from focusing solely on the individual harm caused to someone on social media could move to a focus on the threat to marginalised groups and wider society. Communities as a whole would benefit from safer and more inclusive practices on social media. The current system does not categorise ‘incels’ as an extremist ideology, but doing so would recognise the real risk of it and allow for further monitoring.

It is clear that influencers and algorithms are targeting young men and teaching them that women are to blame for all of their struggles in society. The Bondi Junction stabbing is just one terrifying reminder of the consequences of toxic masculinity and the spread of incel ideology. The stabbing calls for the urgent need to address the root of misogyny and hate that grows on social media and asks society to recognise the broader social implications and the harmful impacts that patriarchy and hegemonic masculinity perpetuate. The rise of incels and online radicalisation stands as a sign of a deeper crisis surrounding masculinity, one that demands urgent attention calling for the protection of women, as well as men as we integrate them back into society. While initiatives like the Talking Masculinities Project offer glimmers of hope in educating and empowering individuals to recognise and challenge toxic beliefs, much more needs to be done.

It is vital that as a society we confront the issue of misogyny and hate towards women in order to protect each other. These issues have gone on long enough without real solutions despite desperate calls for them. The frequency of violent crimes against women being reported on the news and social media is disgusting, disappointing and presents a sobering portrait of contemporary society. To combat this issue would not only validate women's experiences but also see to it that society comes together to engage in critical self-reflection and collective action. The path forward requires an approach that combines education, intervention, and advocacy to foster a more inclusive and equitable society. It is only down this path that we as a society can hope to confront the scourge of misogyny, incel ideology, and male radicalisation on social media- paving the way for a future that has empathy, respect, and gender equality.

References