Incarcerated Women

Media Representations vs Reality

Content warning: this story covers topics such as murder and sexual assault

This story aims to focus on women within incarceration systems, as well as their representations within the media.

Firstly, we focus on New Zealand prisons and the overrepresentation of Māori women. Secondly, we dive into the experiences of incarcerated transgender people to highlight some shortcomings in New Zealand's prison system.

We then dive into how the entertainment industry and mainstream media portrays incarcerated women, with an emphasis on intersectional identities. We analyse gender bias within news media, to display imbalances in how men and women are represented in the justice system.

Māori Women in Prison

An Intersectional Lens in New Zealand's Criminal Justice System

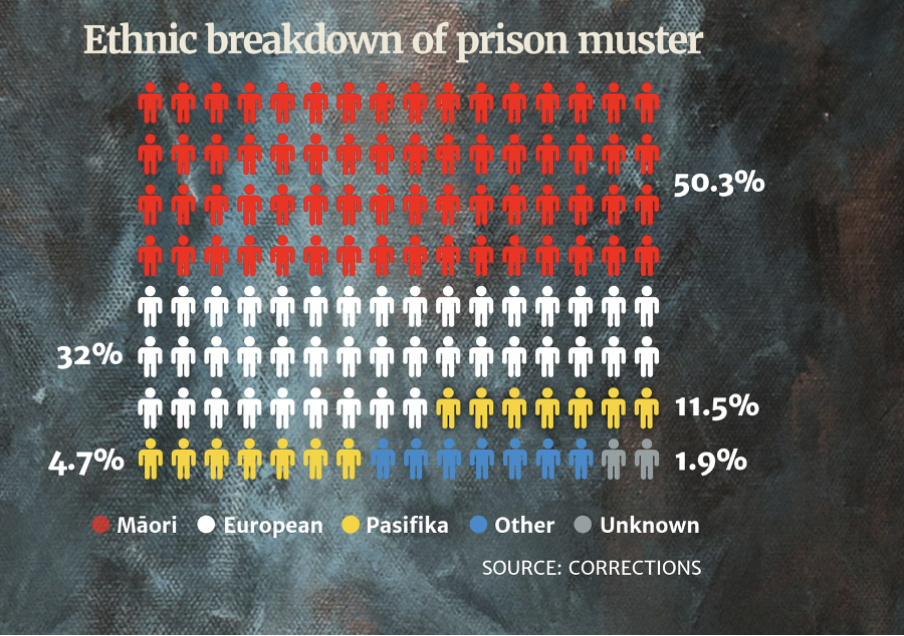

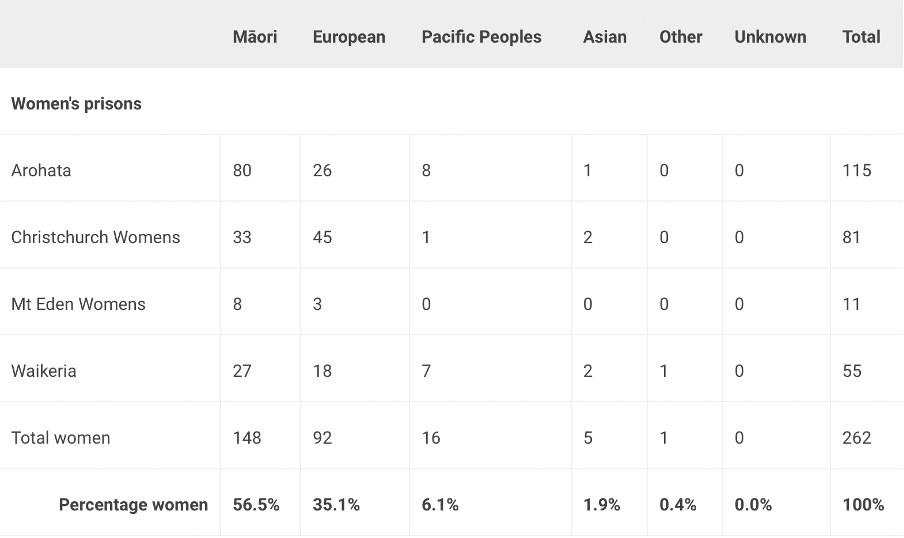

In New Zealand Māori are over-represented in the criminal justice system. In 2021 alone, 56.5% of Māori were sentenced inmates by institution compared to 35.1% of Pakeha . This means that Māori make up 50% of New Zealand’s prison population, despite only accounting for 15% of the population. Māori women make up 63% of the female prison population where 18% of Māori convicted of a crime receive a prison sentence, compared to 11% of Pakeha.

However, the crimes that Māori women are convicted for are likely tied to their socio-economic backgrounds, educational inequalities, poverty, and experiences of trauma and substance abuse. The mis-representation of Māori women and people of colour in the Criminal Justice System uncovers the existing biases that consequently enforce racial imbalance.

7.3% of Māori women are convicted of low-level crimes such as drug possession or drug use who as well experience prison time compared with 2% of Pakeha. Within two years of being released from prison, two thirds of Māori have been re-institutionalised, whereas for Pakeha, just over half.

Transgender + Non-Binary Rights in New Zealand Prisons

In 2020, the Department of Corrections said there were around 30-40 transgender individuals currently imprisoned in New Zealand. This section explores trans prisoners' rights, as well as their experiences in prison.

What Rights do Transgender People Have in New Zealand's Prison System?

Aotearoa New Zealand has some specific legislation in place to protect the rights of transgender individuals who are imprisoned.

Typically, women and men would be separated in prisons based on the recorded sex on one's birth certificate. This means that in many cases, trans individuals would be sent to prisons according to their assigned gender at birth.

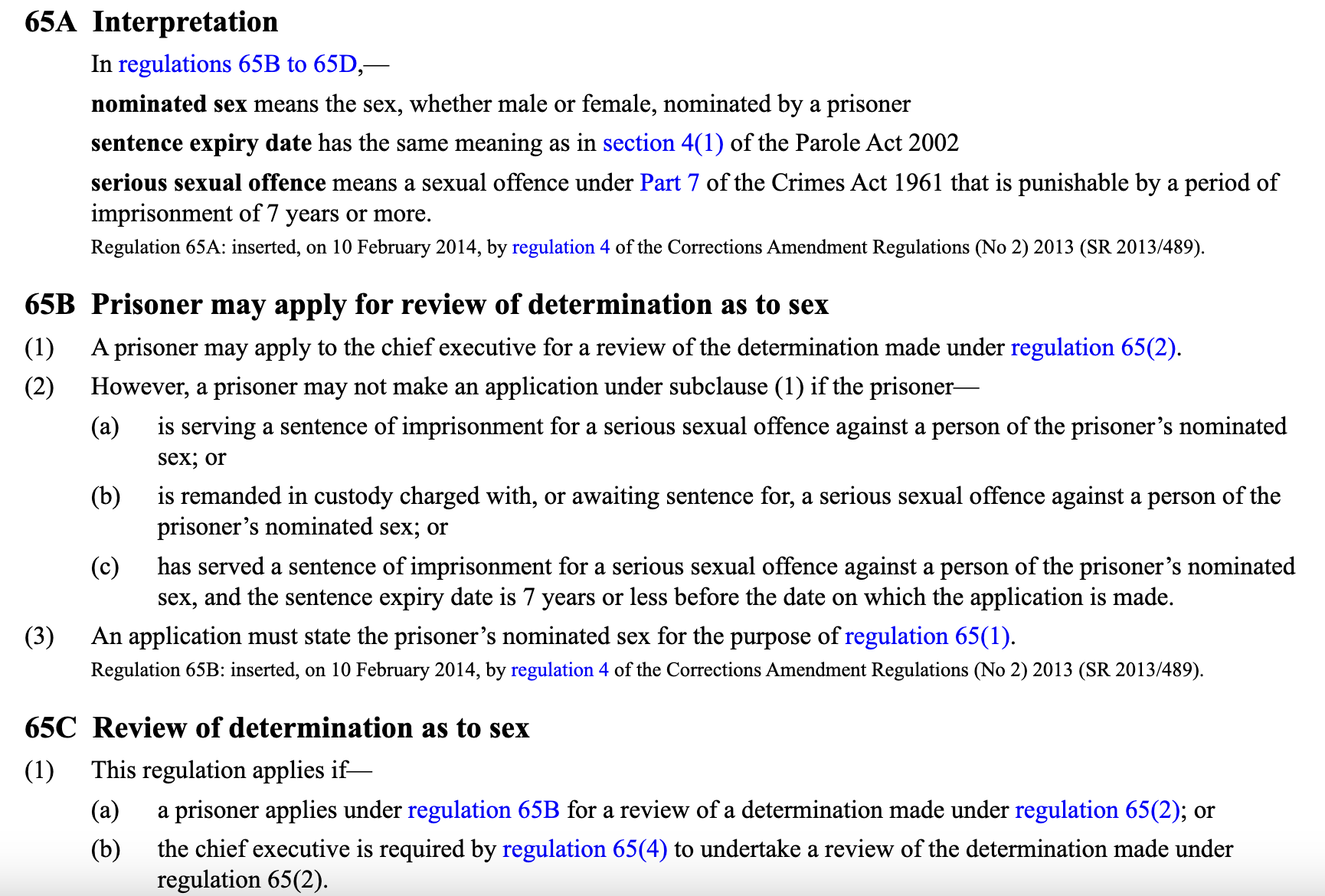

However, clauses 65 to 65E of the Corrections Regulations 2005 specify that an individual may ask to determine their nominated sex, in order to be put into a prison that matches their gender identity (or a prison they believe they would be safer at). If a transgender prisoner is not transferred to a different prison, they still reserve the right to have this reviewed. The decision to transfer prisons is determined by factors such as evidence of one's gender identity/expression outside of prison, a doctor's opinion, and the safety of other prisoners as well as their own.

The Department of Corrections recognises non-binary people as those without a nominated sex. Non-binary and intersex people have the same right to ask for a review regarding what prison they go to, however this process begins automatically based on the recorded sex on their birth certificate.

However, the Corrections Regulations 2005 also states that an individual may not apply for a change in prison if they are "serving a sentence of imprisonment for a serious sexual offence against a person of the prisoner’s nominated sex" (Clause 65B (2))

The Prison Operation Manual states that transgender prisoners must be in single cells, however they can choose to share a cell with another trans or non-binary prisoner if they both agree. The final decision is reserved to the prison.

The Corrections Regulations 2005 Outlines transgender prisoner's ability to choose their nominated gender and what prison (men's or women's) they are sent to.

Maintaining One's Gender Identity in Prison

Section I.10.1 of the Prison Operations Manual states that "Being trans is not a lifestyle and is not a choice. A person’s ability to identify with a particular gender, or no gender, must be respected."

Transgender prisoners's chosen names and pronouns must also be used by the prison and its staff when communicating with prisoners, as well as in reports, offender notes, etc.

Furthermore, transgender prisoners are also provided with clothing and items such as binders and tucking tape in order to help them maintain their identities in prison.

Are the Rights of Trans Prisoners Being Respected?

There are a number of cases in which New Zealand transgender prisoners have reported mistreatment, discrimination, or had their rights ignored by prison staff.

An RNZ article from November of 2020 outlines the experiences of transgender woman Anahera (name changed for privacy) in Mt Eden prison, an all male prison.

On her first night double bunking, she was nearly raped. Three years later, she was transferred to Auckland Prison/Paremoremo and was raped twice.

"And her words to me, because I'll never forget this, was, 'What do you expect? You're in a men's prison. If you don't like it, go to the women's.' So I actually had to go back into the unit with the person who done it. And then when I complained, they wanted to move me out. Because they saw me as the problem."

Excerpt from RNZ Article

For the majority of her sentence, Anahera was in an all-male prison, but placed in segregation away from the other inmates - which she found isolating and affected her mental health negatively.

On top of this, some prison officers often referred to Anahera with various derogatory names such as"it", "homo", "gay" and other slurs. In another incident, she was strip searched by multiple female officers who were then overheard talking about her genitalia afterwards.

Another RNZ article from April 2020 outlines the experiences of a trans man who was denied his right to choose what facility he would be sent to.

While in his holding cell, trans man Lucas (name changed for privacy purposes) asked to be placed in a female facility and to be searched by female officers. He expressed concerns over his personal safety - being a target of physical or sexual assault - if he was sent to a male prison.

Lucas was signed relevant documents at court in 2017, and another in his holding cell in 2019. However, the moment he left his transfer truck he found himself at Mt Eden Prison - an all-male corrections facility. At that point, the Department of Corrections claimed that no such document existed on his file.

Lucas was eventually transferred to Auckland Women's Prison where he felt more respected and comfortable. Over three months later he was released and placed on house arrest, and Lucas filed a complaint to the Office of the Inspectorate stating the Department of Corrections' actions leading to concerns over his personal safety.

'"They have not followed process at all," Gender Minorities Aotearoa national coordinator Ahi Wi-Hongi says.'

"The second I got out of the truck, my first question was 'Wait a minute, is this a men's prison?' and the guard was like 'Where else would you f****** be?'.

Excerpt from RNZ article

These two cases of trans prisoners' experiences are only a small percentage of the overall transgender population within New Zealand's prison system. However, they outline that despite the legislation in place to protect transgender rights, the Department of Corrections still does not follow process and respect these rights with consistency. There are multiple articles outlining experiences of trans prisoners being discriminated against, being refused hormone therapy, and not being sent to their preferred prison facilities.

The presence of transgender individuals in New Zealand prisons necessitates a more rigorous process to ensure the rights and safety of transgender and non-binary prisoners.

Does Entertainment and Social Media Affect the Way in Which Society Responds to Real Incarcerated Women?

"Mugshawtys"

Objectification of Prosecuted Women

The ’male gaze’ is an influential narrative that has forced a culture in society to objectify incarcerated women in a sexual manner. These narratives have led on to be portrayed in social media accounts, comments, shares, and posts for heterosexual consumption.

The Instagram account 'Mugshawtys' is an example of how the actions of incarcerated women are disregarded with the exception of their physical appearance due to the objectification from wider audiences.

Moreover, this is an example Instagram post from the Mugshawty's account presenting a mugshot of a woman arrested for engaging in prostitution. This is also an example of the male gaze at play where prostitution as a form of labour is disregarded within the interest of sex rather than validating women and minimising instances of harm. The comments discussed under this Instagram post tend to invalidate feminist movements within the progress for social change and sexualises these women as objects of desire.

Physical attractiveness has become a driving force in how decisions are made for much of society. There are many connections between aesthetic beauty and judgments about an individuals morality. This stems from the ‘beauty is good’ stereotype and the negativity bias associated with unconventionally attractive people or the idea that ugly is bad. The term 'pretty privilege' is prevalent in this case because audiences are drawn to the physical appearances of incarcerated women which ultimately concludes societal responses and offers women 'a pass' for their criminal behaviour.

These existing narratives within social media regarding incarcerated women is a concern to the overall treatment of women in society. There is a continuum within the act of objectifying and sexualising women where feminist movements have been striking for change for the liberation of women. However, there is a need to recognise how the extent of entertainment productions and platforms disvalue the actions of convicted women for the desire of individual pleasure.

Instagram Handle: https://www.instagram.com/mugshawtys/

Orange is the New Black

Fictional Portrayals of Women's Real Experiences in Prison

Netflix has become a milestone in the production, distribution, and consumption of entertainment. In shows such as Orange Is The New Black and its purpose towards producing entertainment to its watchers raises concern towards the way in which the show is constructed and narrated that portrays the reality of incarcerated women experiences. In turn this calls for advocacy in social change and a space for victim's voices to be heard.

Consequently, the show and its representations has become a catalyst for discussions about race, gender, class sexuality, inequality of justice, and the carceral state. These patterns located in Orange Is The New Black represent dominant ideologies within the culture that created them where characters that are portrayed impacts how those characters and the social groups to which they belong to are seen by viewers. Furthermore, these representations influence the messages that viewers take away from the series and ultimately ignores the real-life issues of incarcerated women.

Image from The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/jun/15/orange-is-the-new-black-season-four-review

The show was particularly praised for its nuanced representation of the transgender character Sophia Burnet, played by trans woman Laverne Cox.

The show details Sophia's experience in prison having her hormones reduced, due to the prison not recognising her hormonal therapy as 'important'. She also faces other forms of discrimination in the prison system, such as being placed in solitary confinement for weeks, due to her being perceived as a potential threat to the other inmates.

Beyond this, the show also handles her personal transition story with nuance and a level of realism.

Actress Laverne Cox states that the writers were intentional in portraying Sophia's character with a level of realism and accuracy to real transgender women's experiences.

Characters such as Sophia Burnet are a positive step in transgender representation, as it highlights real trans issues to mainstream audiences. This is important especially in the context of Orange is the New Black, as it can help challenge stigmas and assumptions about incarcerated women in the US, especially those with intersectional identities.

"...Sometimes trans women are placed in men’s prisons, where they put us in solitary confinement, which is cruel and unusual punishment allegedly for our protection... This is what happens to so many transgender people who are incarcerated every single day." - Laverne Cox

News Coverage vs

Real Life

Cyntoia Brown

At the age of 16 years old, Cyntoia Brown was facing life in prison for murder. She was a victim of sex trafficking and when she made her escape from her perpetuator, she made the decision to defend herself in order to survive. The media would then go on to portray her as a murderer and a criminal who was sentenced to life rather than a teenage girl who is a survivor of rape and sex trafficking.

News Coverage

Immediately, the news began to televise her trials and keep the public updated with any information they could grasp. Although the news is a way to stay informed with what is going on around us, we develop a bias based on what we are shown. Along with updates, there are specific words chosen when displaying Brown's trial and situation. She was often referred to as a "murdered" and a "criminal" and when her image was broadcasted it would always be Brown in an orange jumpsuit as well as cuffed and restrained. This would lead the media to already criminalizing her and pushing the notion that she was guilty without a further extent to the story.

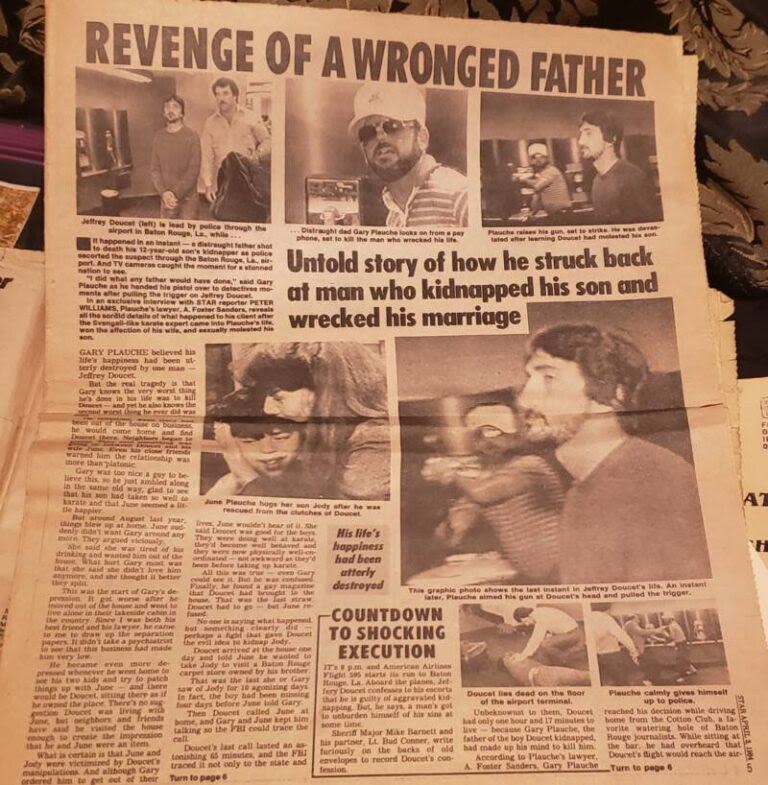

Gary Plauche

Gary Plauche, a father to Jody Plauche, had taken matters into his own hands. Jody had been kidnapped and molested by his former karate instructor. Once the perpetrator had been captured and arrested, it was not enough in the eyes of Gary. He had waited for the cops to bring the perpetrator around in the airport and then shot him which led to his death. Gary faced a sentence of 7 years and 5 years with probation.

News Coverage

Gary had a very different media presence. News articles came out with the words and sayings such as "heroic" and "father's justice" and even "protector" as they referred to Gary and his situation. As the news coverage made an effort to keep the public involved, the images they used would always be of Gary smiling or with his child. The media had made it known that this was a father protecting his son rather than displaying it as a murder case.

The Gender and Racial Bias

There is no secret that there is a significant difference in the way women and men are presented on media platforms, whether it be positive or negative events. The journalism field studies have shown that women make up about two-thirds of the field, however, they are underrepresented in the newsroom and broadcasting. As men hold more positions in these categories, we see a pattern where the information showcased is catered to the male viewers. We see it occur in the previous cases that were mentioned, as Cyntoia Brown's reference were negative while Gary Plauche's were positive and affirming. GMMP has provided data that shows women only make up about 24% of people heard, read about, or seen in newspaper (Geertsema-Sligh, 2018). When it comes to violence against women, we see the massive shift in representation and assigning blame to the victim. Often, news about violence against women are skewed. We can see in matters of rape cases where rape is seen as sex or lust or women provoking the assault. In Cyntoia's case, news presented her as a murderer and a thief because she took the money that was given to her through the sex trafficking act. By misleading the public away from the rape of a minor, they are diminishing the victim's experience and portraying women a specific way.

Intersectionality is crucial when it comes to media coverage. Cyntoia is not only a woman, but she is a Black woman. Her identity is used against her as news coverage typically belittle women who have experienced sexual assault or victimized in sex trafficking, however, as a Black woman she is now presented as the perpetrator. Black individuals are typically represented in a stereotypical way where the news coverage feeds into the negative connotation of Black people and crime. Drawing from Vanessa Hazell and Juanne Clarke from "Race and Gender in the Media," Black women are stereotypically presented to be seductive, sexually aggressive, and threatening in media. As news coverage assigns blame to Cyntoia through the verbiage in the way they address her, they no longer showcase her as a victim but the criminal who committed a murder and caused a man to seek sexual favors from her. On the other hand, we see the case of Gary Plauche, who is a White man, is portrayed as hero for defending his son. The image of a White men is typically seen as the "default setting" who hold a hierarchy within society. When inspecting both cases we see how the media coverage for each cases has a bias. Although Brown acted in self-defense and was a victim, Plauche Plauche stalked his son's molester and created a plan to kill him. However, Plauche received a sentence of 7 years while Brown received life in prison. The way they were represented to the public through media had a role in their sentencing, their treatment, and their life.

To this day...

Eventually Brown had to fight for clemency which was granted only after she had spent 15 years in prison. The media might not have directly placed Brown in prison for those 15 years, however, we see the affect that news coverage and overall media plays when shaping or forming opinions and thoughts on certain situations and people. While the affects of the media are proven to show the racial and gender biases within them, how could it not affect an entire trial?

References

Corrections Regulations 2005 (SR 2005/53), 65 (2005). https://legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2005/0053/latest/whole.html?search=ts_act%40bill%40regulation%40deemedreg_Corrections+Regulations+2005_resel_25_a&p=1%2f#contents

Going to prison. (n.d.). Community Law. Retrieved May 9, 2024, from https://communitylaw.org.nz/community-law-manual/test/human-rights-and-discrimination/going-to-prison/#:~:text=If%20you

Lockett, D. (2015, June 24). Orange Is the New Black’s Laverne Cox on Why Playing Sophia’s Shocking Punishment Was an Out-of-Body Experience. Vulture. https://www.vulture.com/2015/06/laverne-cox-orange-is-the-new-black-sophias-shocking-punishment.html

Murphy. (2022, April 4). Corrections “have not followed process at all” for trans prisoner. RNZ. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/464580/corrections-have-not-followed-process-at-all-for-trans-prisoner

Murphy. (2024, May 9). Guards called me “it”, “homo”, discussed my genitals - trans prisoner. RNZ. https://www.rnz.co.nz/programmes/here-we-are/story/2018773312/guards-called-me-it-homo-discussed-my-genitals-trans-prisoner

Prison Operations Manual. (2016, December 5). Www.corrections.govt.nz. https://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/policy_and_legislation/Prison-Operations-Manual

Jackson, S. A., & Gordy, L. L. (Eds.). (2018). Caged Women Incarceration, Representation, & Media. Routledge.

Chavez, M. (2015). Representing us all? Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Orange Is The New Black. ProQuest.

Stuff. (2018, May). Crime and Punishment. https://interactives.stuff.co.nz/2018/05/prisons/crime.html#/

Department of Corrections. (n.d.). Inmate Ethnicity by Institution. https://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/statistics/corrections-volumes-report/past-census-of-prison-inmates-and-home-detainees/census-of-prison-inmates-and-home-detainees-2003/2-inmate-numbers-by-institution/2.4-inmate-ethnicity-by-institution

Hazell, V., & Clarke, J. (2008). Race and Gender in the Media: A Content Analysis of Advertisements in Two Mainstream Black Magazines. Journal of Black Studies, 39(1), 5–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40282545

Shor, E., van de Rijt, A., Miltsov, A., Kulkarni, V., & Skiena, S. (2015). A Paper Ceiling: Explaining the Persistent Underrepresentation of Women in Printed News. American Sociological Review, 80(5), 960–984. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24756352

Willingham, B. C. (2011). Black Women’s Prison Narratives and the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Sexuality in US Prisons. Critical Survey, 23(3), 55–66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41556431

Geertsema-Sligh, M. (2018). Gender Issues in News Coverage. In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies (eds T.P. Vos, F. Hanusch, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh and A. Sehl). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0162