Gender Performativity

A Societal Account of Gender

Overview of Gender Performativity

Gender performativity, a theory sprouting from the philosophy work of Judith Butler is the idea that gender is located in the acts that constitute it. It is the idea that gender is made up of acts that mark people as male or female.

These acts can be behaviours or clothing, hair, and makeup and through repetition of these acts, gender is firmed and finalised. Going against these norms often can result in discrimination.

An example of this would be a man wearing a dress. The act of wearing a dress has been assigned to women through repetition of women wearing dresses and men not wearing dresses. This occurs from individual to individual and society to society.

Butler describes gender as a social construct that can change over time and can differ from society to society. These ideas can be seen when looking at the colour pink and how it was originally a described as a man’s colour, or how it is normal to see to men hold hands in public in Iran, while in New Zealand this is not so common.

Definitions of masculinity and femininity vary, and acts and roles of gender vary according to this.

Photo by Norbu GYACHUNG on Unsplash

Sex vs Gender

Photo by Michael Prewett on Unsplash

Photo by Michael Prewett on Unsplash

Sex

The biological composition, defined as female, male, or intersex.

Photo by Delia Giandeini on Unsplash

Photo by Delia Giandeini on Unsplash

Gender

The socially constructed roles attributed to sexes based on behaviours and identities.

“One of the things I’m proud of is that I think that I’ve helped to provide frameworks to talk about it, narratives that are now available to other people”

- Bo Laurent, intersex activist

Gendered Since birth

From an early age most children are taught that gender and sex are the same and are binary.

Around age two children start to become conscience of the differences between boys and girls. Around age three children label themselves as either boy or girl and by age four most children have a sense of their gender identity.

Gender roles are also taught at an early age. Boys like trucks and girls like dolls. Boys like the colour blue and girls like the colour pink.

Girls are either known as "girly girls" (those who play with dolls, dress up as princesses, and like pretty, pink things) or as "tom boys" (those who don't like dresses, enjoy getting muddy, and who are more reckless).

These categories make it difficult for children to understand that you can be a girl and enjoy getting muddy, for example, or that the sex you were assigned at birth does not have to limit how you represent yourself. This idea also makes children grow up to feel "not normal" if they don't fit into the "correct" category.

It is these ideas that create and impose the idea that certain acts are related to gender and because children know no better it becomes true only strengthening the idea that gender is bound and or performative.

Photo by DAVID ZHOU on Unsplash

Photo by DAVID ZHOU on Unsplash

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Photo by Heather Suggitt on Unsplash

Photo by Heather Suggitt on Unsplash

Photo by Ben Hershey on Unsplash

Photo by Ben Hershey on Unsplash

Gender in School

Education systems are notorious for reproducing a gender binary. Notable aspects of this include uniform, and institutions in general.

Often, male students are required to have neat, short hair that doesn't touch their ears, whereas female students are allowed their hair long. This differentiation in uniform only occurs on the basis of gender, as there is no other reasoning behind such regulations.

When discussing the gendering of institutions, the separation of school based on sex is a key factor. Single sex schools and co-ed schools play into a number of gender roles, such as the type of work genders should do, and the access to resources.

In a single-sex school for females, there tends to be a heavy enforcement on the priority of the arts, while access to scientific studies are limited or not encouraged to the same extent as literary subjects or artistic subjects. This contrasts to the push of leadership within single-sex schools for males, as well as the emphasis on subjects involving mathematics and sciences.

The gendering of education systems tend to discourage breaking gender binaries from a young age, and rather expect young individuals to conform to gender roles within their adolescence. Furthermore creating a gender divide going into adulthood.

Contemporary Gender and Society's Response

As social media has become a more prominent aspect of contemporary society, individuals have been able to connect with other people, groups, and spaces to explore themselves and how they wish to identify to others.

Social media allows both connection with a wider range of people, and some anonymity within these connections. This makes for a more comfortable space as people explore who they are, specifically, their gender.

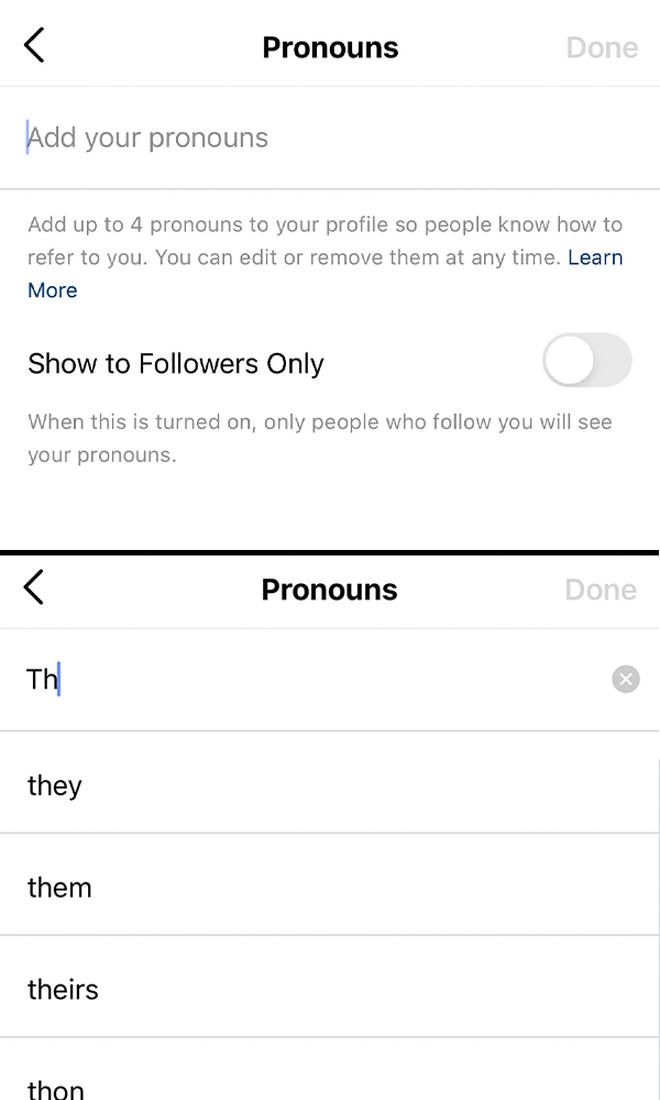

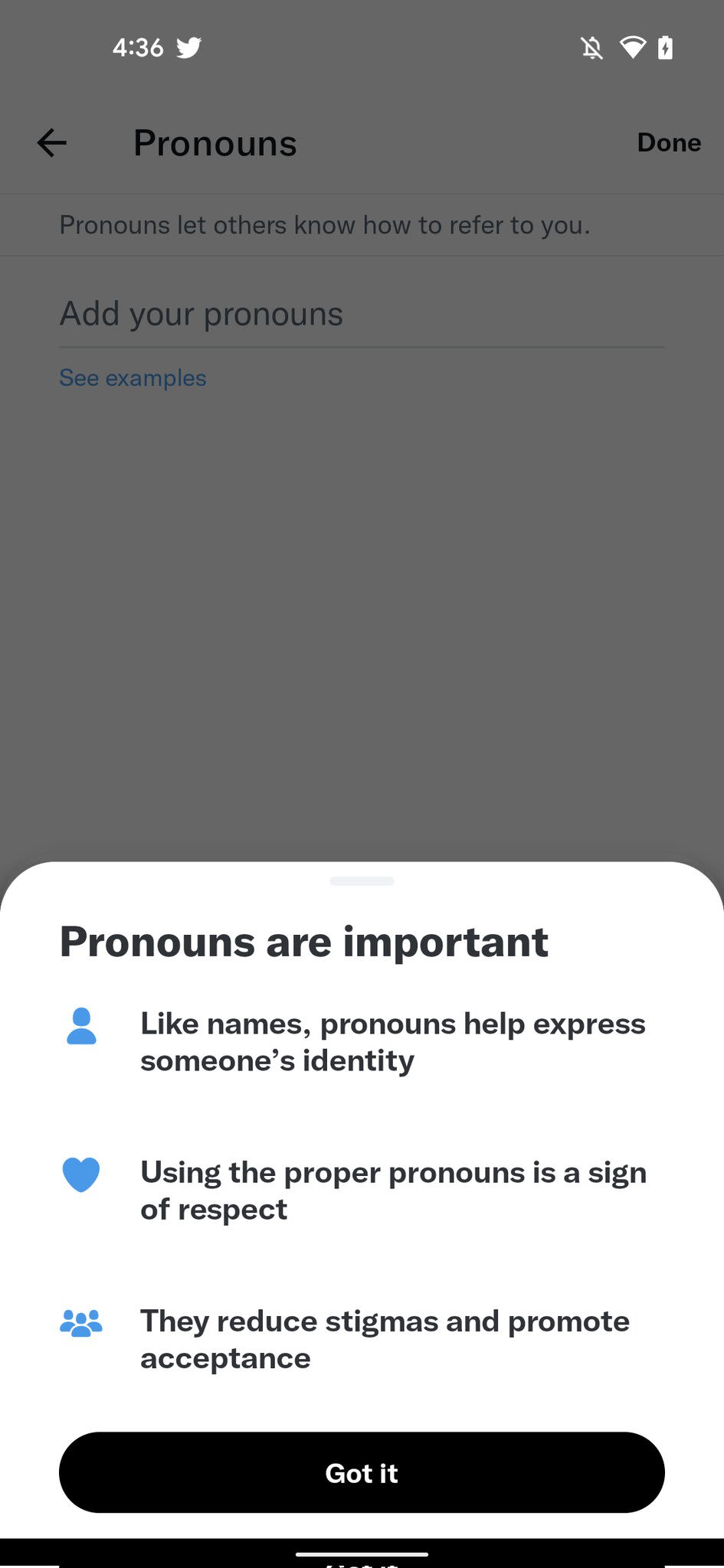

Since 2021, apps such as Instagram, Twitter, and Tiktok have allowed users to display their preferred pronouns in their bio. Pronouns are one way an individual can feel they fit into the categories society has created.

Instagram added the option to display pronouns in a user's bio in May 2021. Options include she, he, they, ze, ve, and more.

Also in May 2021, Twitter introduced pronouns for user's bios. Options include she, he, they, ze, xe, ve, and more.

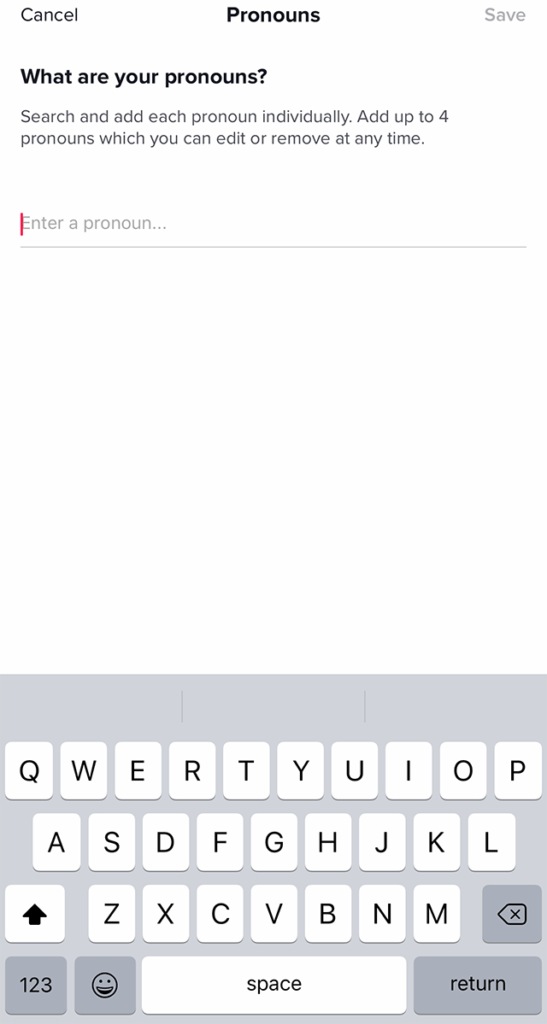

Tiktok

In January 2022, Tiktok also added a pronoun option to their platform for app users.

While choosing pronouns different to ones birth-assigned sex allows some individuals to feel a sense of belonging, many people don't understand the difference between sex and gender, they don't understand what it's like to experience dissonance between the two, or they blatantly discriminate those who do.

Discrimination on the basis of gender is not uncommon in contemporary society, and transgender, gender non-conforming people, and allies from across the world are fighting back - one way in the form of protests.

Hypocrisy in Gender Performativity

The context of gendering clothing is specifically interesting. There has been a long lasting association between the clothing in which a female ‘should’ wear, and the clothing in which a male ‘should’ wear.

This has enforced a binary onto the relationship between gender performance and clothing. Examples of this include women in skirts and dresses, as opposed to men in shorts and pants.

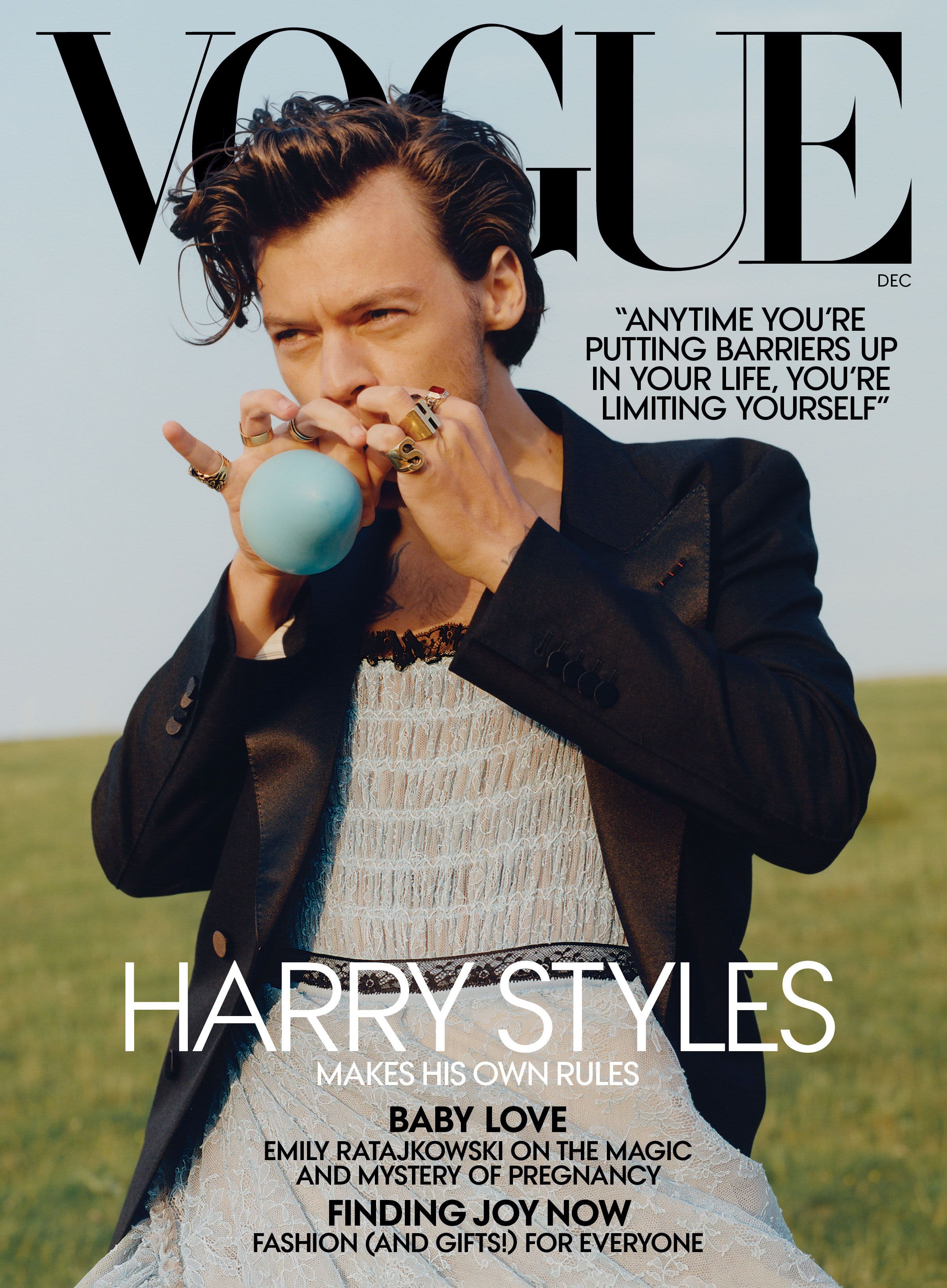

In 2020, Harry Styles featured on the cover of Vogue's December edition. He was the first solo man in history to feature on the cover, and while the response was overall supportive, some still had negative opinions to voice.

The hypocrisy involved in Harry Styles' Vogue cover can be exhibited through the treatment of him following the feature. Styles received a mixture of positive and negative backlash from the feature, yet was not sexualised following such.

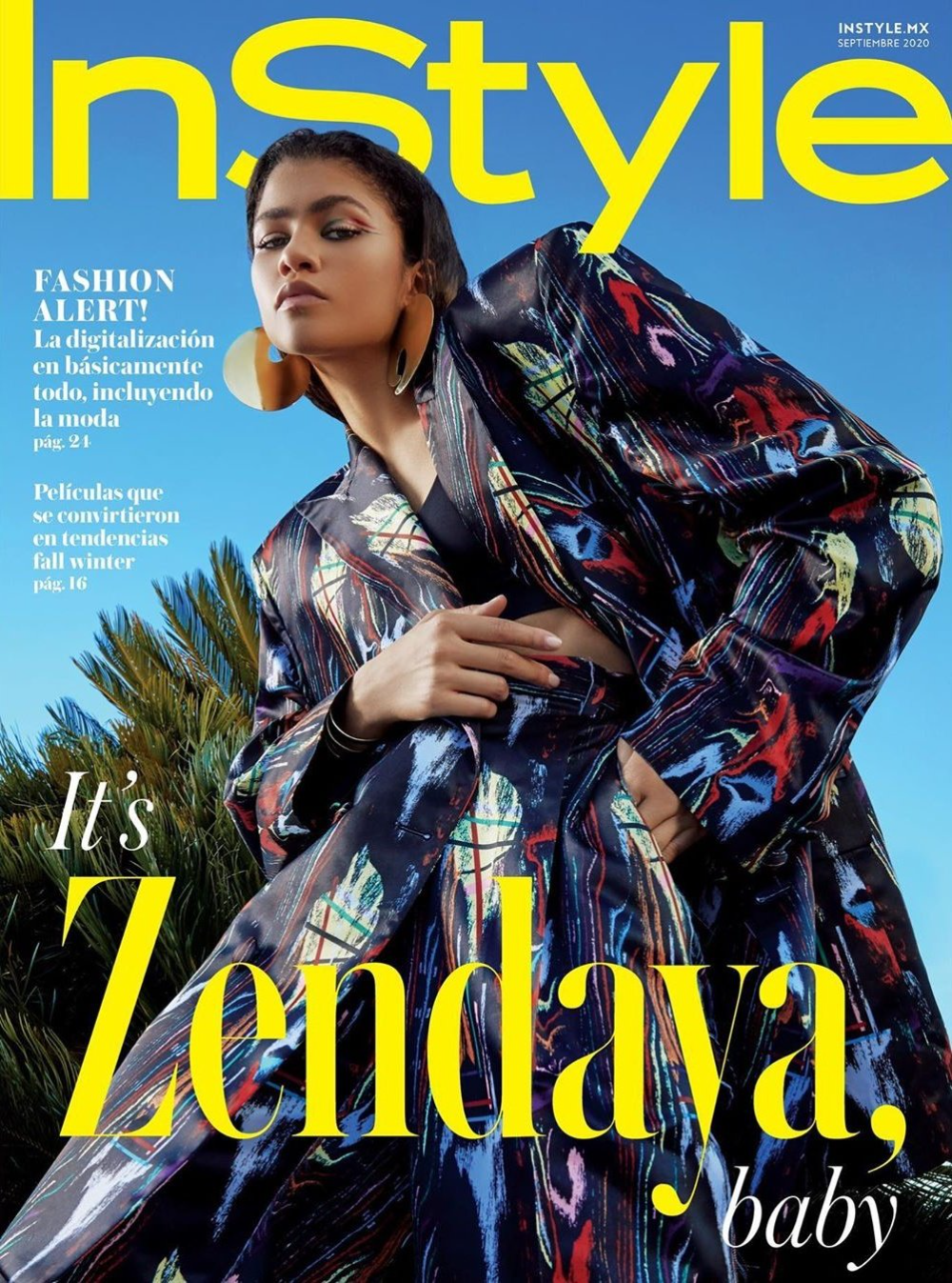

This is a direct contrast to the treatment of female celebrities such as Zendaya, who upon wearing an oversized suit on the cover of InStyle September 2020, was oversexualised by viewers.

Harry Styles as the first solo man to appear on the cover of Vogue

Harry Styles as the first solo man to appear on the cover of Vogue

Although the performance of gender is becoming more blurred than bound, there is still an overwhelming negative attitude towards the breaking of these binaries.

Actions such as gendering colours and gendering clothing keep these binaries in place, yet the use of celebrities and public figures slowly breaks these binaries.

Gender performativity is a cycle which is desired to be broken, yet the stigmas surrounding challenging normalities discourages us from breaking these norms. Because of this, popular figures are the most useful figures to challenge these binaries and set new cultural normalities.

References

Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), pp.519–531.

Choi, S. (2019). Judith Butler’s gender performativity and its theological application. Theological Forum, 96(1), pp.265–293. doi:10.17301/tf.2019.06.96.265.

Meyerhoff, M. (2014). Gender performativity. The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality, pp.1–4. doi:10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs178.

Paechter, C. (2010). Tomboys and girly-girls: embodied femininities in primary schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 31(2), pp.221-235. doi:10.1080/01596301003679743

Cossman, B. (2018). Gender identity, gender pronouns, and freedom of expressions: Bill C-16 and the traction of specious legal claims. University of Toronto Law Journal, 68(1), pp.37-79. doi:10.3138/utlj.2017-0073