Gender in Beauty Ads

Decoding the Glamor Game

The beauty industry over time has continued to perpetuate unrealistic standards of beauty through multiple areas of its industry. Advertising serves as a tool through which gender norms are reflected, reinforced, or broken. By focusing on beauty products and the new wave of challenging norms, fashion advertising and implications for women, the pink tax, and the serge of pro cosmetic procedure content, we will analyse gender in advertising.

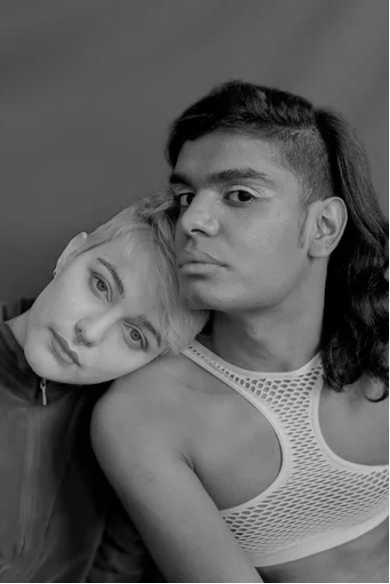

Unisex Representation

For years, the mass-market beauty and personal care industry has perpetuated gender stereotypes, evident in products like thick blue disposable razors for men and dainty pink ones for women. However, newer brands are breaking this mould by embracing gender fluidity in their values. They employ diverse advertising and packaging that vary from old stereotypes. Larissa Jensen, a senior beauty analyst at NPD Group, notes that these brands resonate with younger consumers by prioritizing inclusivity and addressing values such as sustainability and gender neutrality, reflecting a broader movement in consumer preferences.

The origin of this shift can be attributed to innovations in fragrances and perfumes. Products like perfume and lip balm, which are less intrusive, have begun transitioning from gender-specific packaging and marketing to gender-neutral language. This adjustment aims to avoid isolating to either gender.

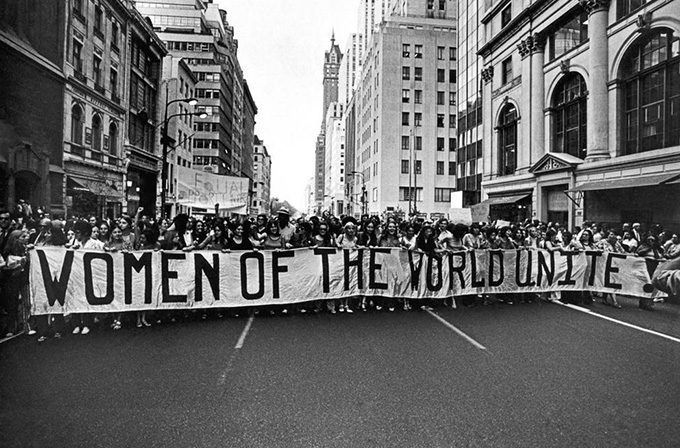

Gender has long been a headline-grabbing topic, but as we step into a new decade, there's a heightened push for equality, shifting away from solely targeting one gender. Embracing gender neutrality, brands are recognizing the benefits of prioritizing function and purpose. We're transitioning into an era where self-acceptance and safeguarding individuality take precedence. The notion that a product must belong to a certain gender or age bracket is fading away. We're rejecting labels like "for him" or "for her" in favour of inclusivity with phrases like "for you" or "for us", transcending traditional gender boundaries.

Illustrating nonbinary advertising, Milk Makeup, a cosmetic brand, launched the gender-neutral marketing campaign #BlurTheLine in 2017. Their target audience encompassed non-binary individuals across seven diverse gender identifications, embracing straight, trans, and genderless identities. The aim was to challenge traditional norms that exclude many individuals. Milk Makeup diverged from the conventional path, reaching out to audiences previously overlooked by cosmetic brands. In addition to promoting nonbinary and gender-neutral initiatives, Milk Makeup provides product designs featuring unisex packaging.

2.

Fashion Advertising and the Implications for Women's Bodies.

Women in High Fashion Advertising

Fashion and its impact as a culture industry cannot be understated, it has held a high standard for ideal beauty, body type, taste, and style as early as 1854 when Louis Vuitton opened its doors for the first time, and is still along others a prominent fashion house. New York Fashion Week: Men’s was only established in 2015, therefore it is fair to say fashion is a commodity predominantly centered on women. So, why is it when we see a high fashion advertisement, it always feels as though we are looking through the lens of a male gaze?

In a world of internet and mass media, advertising is an intrinsic way to maintain relevance as a company, and for fashion houses that have seen the fall of the Berlin wall remaining relevance is to survive. In high fashion advertising isn’t like selling a product, brands tend to sell an experience, a lifestyle that goes along with the ridiculously expensive clothes. Yet in this lifestyle sold in high fashion advertising women are submissive and men are dominant. Regardless of 85% of female majors in top fashion schools in the US, only 14% of fashion brands are run by women. This inequity in employment in a field that is predominantly marketed towards women has led to images and advertising circulated that is extremely damaging to women and young girls.

The contributors of the fashion industry attempt to portray an image of their apparel that is artistic, abstract, and unattainable to ‘ordinary’ people through their advertising. This is an approach of selling the ‘good life’, of the ‘high class life’ as a way of gaining popularity for their clothes. This circulates ideals that the life within the commercials is a life to be desired, the end goal, both physically and relational. This aspiration is clearly damaging to women in multiple ways, yet, in high fashion it is specifically detrimental to how power dynamics are portrays.

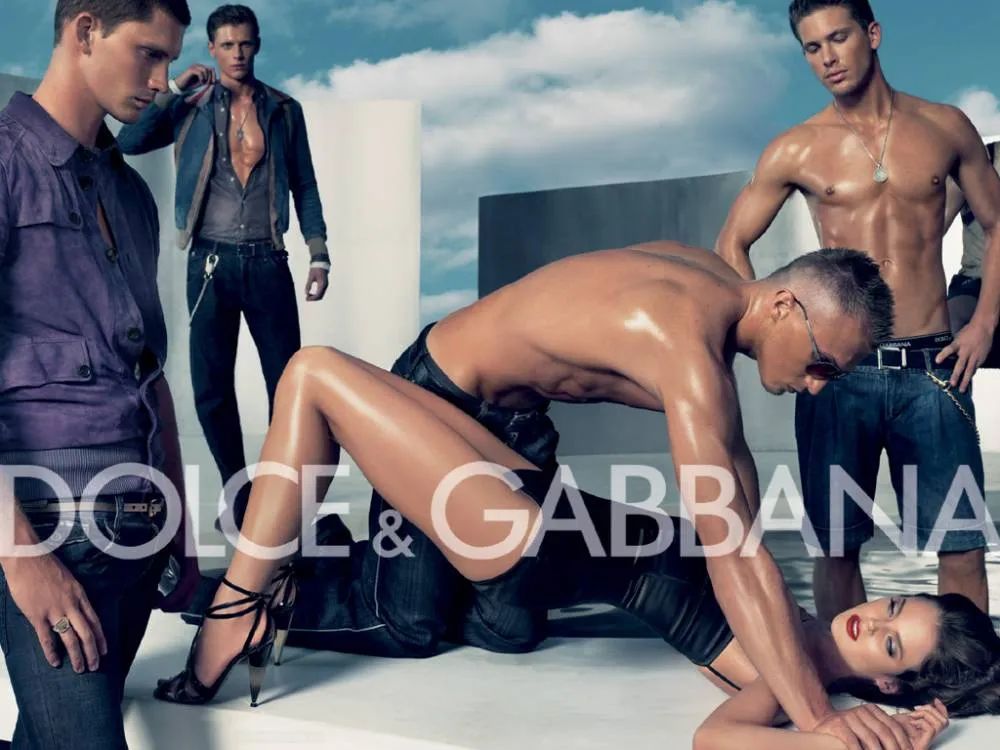

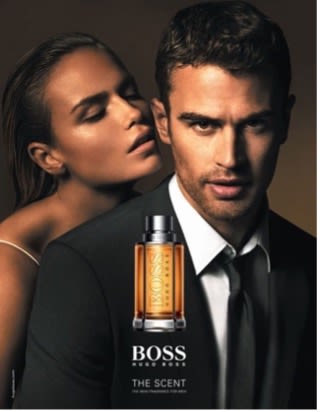

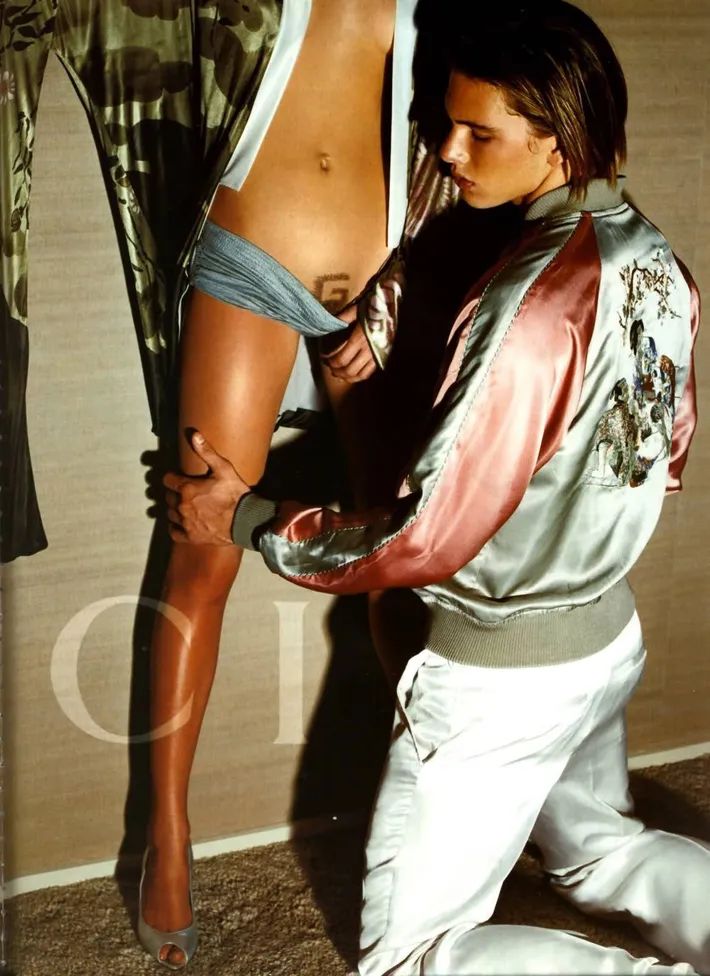

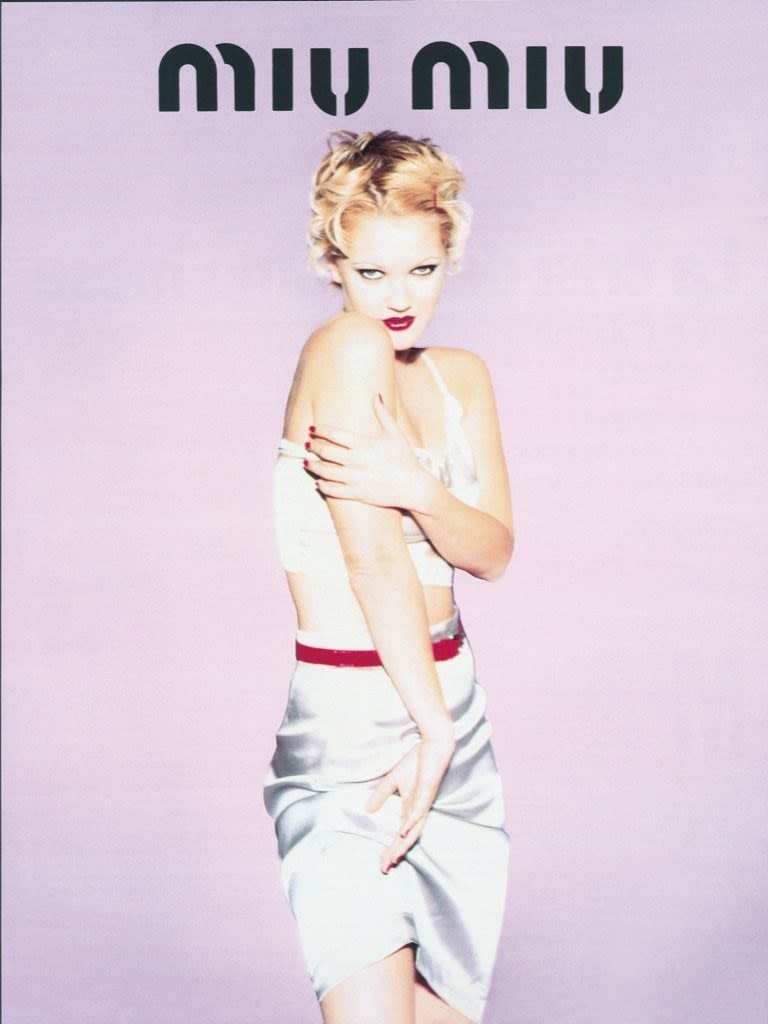

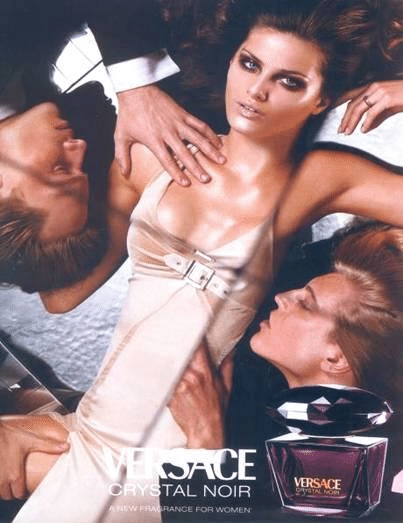

Advertisements for brands like Dolce and Gabbana, Gucci, and Miu miu, it is clear the lens through which they were produced. Women’s bodies are rarely shown as a whole, dismembered only depicting the parts of a woman’s body that are considered desirable. But most notable in these advertisements is the way they produce power dynamic in a heteronormative relationship. It is clear that these advertisements are using sex to sell, by the provocative clothes and suggestive posing by the models. Yet this depiction of sex is through the male gaze as women are continuously placed in a position of submission to their male counterparts. This submission is both to men within the advertisement, and also submission to the men looking upon the advertisement.

These constituents of high fashion ads are used repeatedly regardless of ads target audience, whether men or women. It is obvious these companies are not selling the clothes, but relying on a woman’s desire to conform and meet societies standards of her. These brands reflect and reinforce a society where women are the victim to the power of man. Mulvey states that film reflects and reinforces societal interpretations of sexual difference, and though these are not films, this category of advertising speaks to this theory as there is a clear difference in treatment due to ‘sex’. Women are treated as vessels to display clothes and invite perverse interpretations of the visual text. These advertisements are more often than not produced by a man and reinforcing a male idea of a heteronormative relationships. This continues to put women in a position of powerlessness, and it is important not to understate how this effects real life women. If the media around us, the clothes we buy, and the brand we aspire to wear promote women as objects and place them in situations of ‘violence’ for a photoshoot this allows behaviour to be accepted in society that is harmful to ‘ordinary’ women.

As media images does affect us as individuals and out perception of self, and our media is engulfed by these images of women in these positions, and produced by high fashion brands that set the standard for a desired lifestyle it will continue to have a negative effect on women and restrict them to these outdated positions in society. This way of advertising will continue to hinder feminist movements under the shelter of being a commodity for women.

Women's Fashion Brands on Social Media

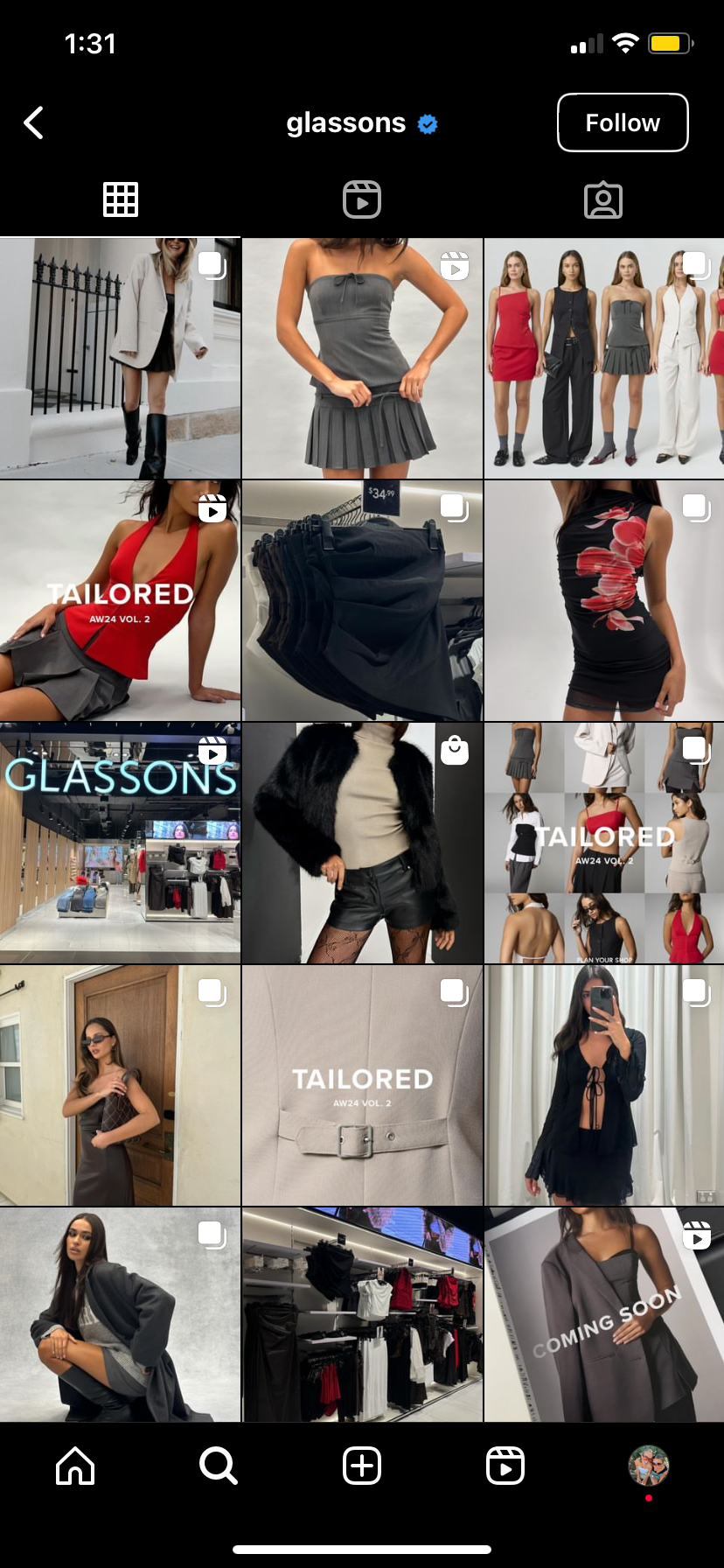

With the development of social media, advertising has taken new forms, companies now assume online accounts that interact with their consumers and promotes their product, in a way personifying their commodity. The fashion industry in particular has taken this approach to social media advertising. More specifically mainstream fashion brands like Glassons, Zara, and Princess Polly have adopted this tactic in order to curate their ideal consumer by taking on this persona as a brand.

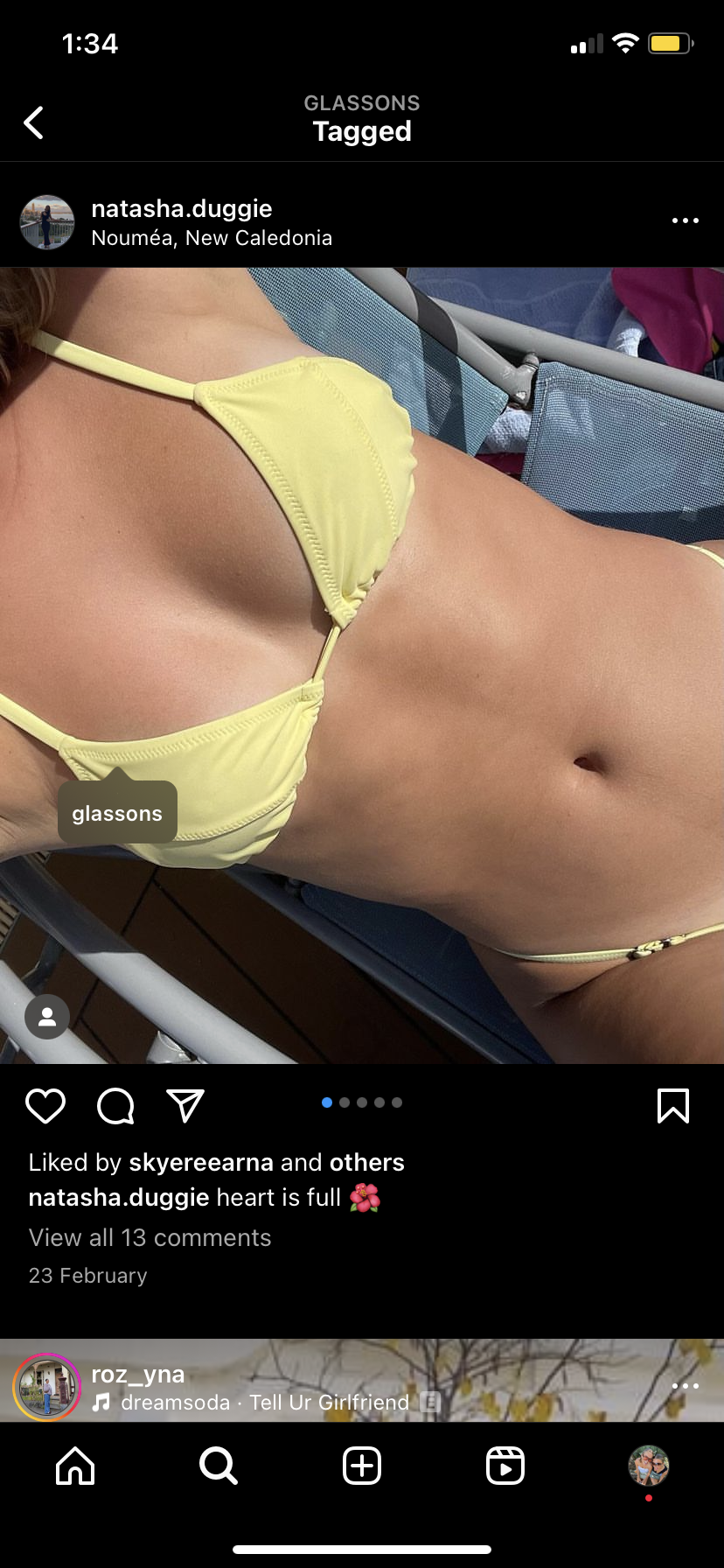

To discuss mainstream brands that have assumed an online persona, Glassons the popular women’s brand is a great example. Their brand was already established in the market as for being quick to trends, and cycling through new styles quickly. Their online persona is an embodiment of their desired target audience. They operate online, specifically TikTok by posting videos of their employees and models trying on the clothes instore for people to see how they would fit. In theory this seems like an effective advertising tool. It allows people to see how clothes would fit without having to try them on themselves, motivating people to buy the clothes quicker. Yet, in reality this form of media and advertising has many implications for body image, specifically on young girls.

Though Glassons is inclusive with the sizing of their clothes on their social media they seem to only show one type of a woman. A woman that is petite, clear skinned, evenly tanned, youthful, and most often white. This portrays a hegemonic western beauty standard that is unachievable for many women. This lack of representation on social media, especially on TikTok during its growing popularity among young people, results in a damaging perception of one’s body image and often body dissatisfaction.

Body image refers to the thoughts and feelings about our own bodies, and body dissatisfaction labels the negative emotions directed at our own bodies (Diedrich 2020). As women, we are taught to place such high importance on our physical appearance, this leads many women to make continuous comparisons of their own bodies to someone they believe to be the depiction of the current beauty standard (Diedrich 2020). It is commonly known that fashion models are used for maintaining this impossible standard. Therefore, a young girl, consuming media on social media could see the exclusive portrayal of a Glassons costumer and believe they must look like that in order to be feel confident and beautiful in their clothes.

Glassons a self-proclaimed inclusive brand maintains a standard of ideal beauty on their social media accounts. This unattainable standard they are promoting as inclusive is preventing women from moving forward in accepting their own body and imperfections. This results in body dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, and in extreme cases eating disorders (Diedrich 2020) and if there in order to move forward and support young adults to accept their bodies it needs to begin in our media and what they are consuming, like fashion advertising.

The Pink Tax

What is the Pink Tax?

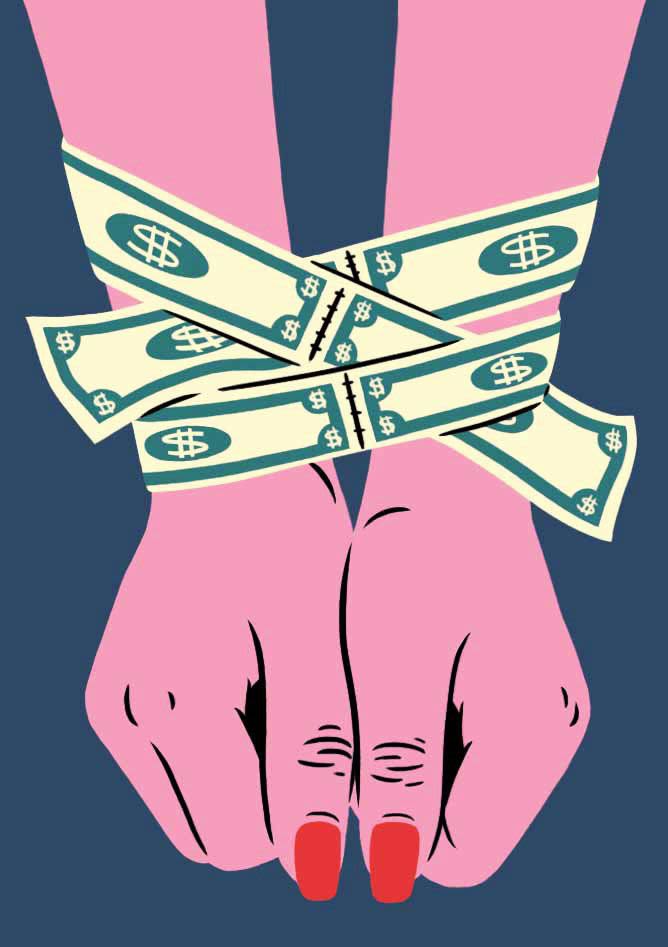

“Pink tax” is the widely known theory that products marketed towards women cost more than their identical counterparts targeted toward men which leads to gender-based price discrimination. This discriminatory practice includes a wide range of products, from personal care to clothing and even certain services such as dry cleaning. The “tax” is in fact not an actual tax but is based off the higher import tariff on women's products.

Studies have shown that products targeted toward women (generally pink and feminine looking), can cost as much as 13% more than similar products for men. In 1994 a study done in California stated that women were paying $1,351 more per year than men. This issue not only perpetuates gender inequality but also places financial burden on women, who already face the issue of the gender pay gap. The pink tax highlights the need for greater awareness and advocacy in pricing relating to gender.

The Pink Tax: Advertising

Pink Tax is becoming a highly talked about issue across social media and it use when advertising for women compared to men. Advertisements often play a pivotal role in promoting products that are subject to the pink tax, generally utilizing gender-specific marketing strategies that reinforce gender stereotypes.

These ads frequently employ color schemes, imagery, and language that cater to gender norms. These techniques further solidify the notion that certain products are exclusively designed for either men or women. Therefore, gendered advertising contributes to the normalization of the pink tax, as it suggests that women should pay more for products catered to their needs simply because of their gender. Gendered advertising and the pink tax perpetuate inequality in consumer experiences and continues the cycle of gender-based price discrimination.

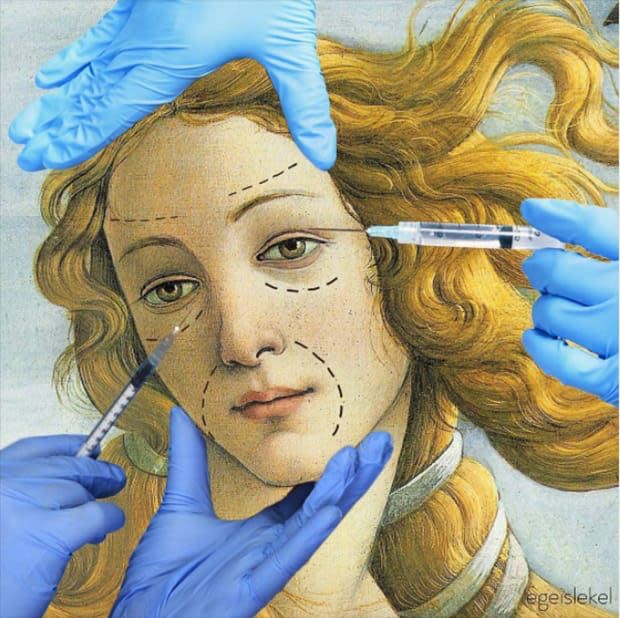

Plastic Surgery Trends

The beauty industry strives on selling women an idealized concept of “aspirational aging,” where women are urged to reinvent themselves in the pursuit of a flawless complexion and a perpetually youthful appearance.

The allure of plastic surgery and cosmetic procedures like botox, brazilian butt lifts (BBLS), and lip fillers has surged in recent times, with a notable uptick during the pandemic, particularly among women. During the lockdown, social media narratives put immense pressure on people to emerge from quarantine with heightened productivity, improved health, and dramatically enhanced physician appearance. Many individuals opted for cosmetic enhancements during lockdown to conceal their transformations and recovery phases. Since 2020, the global cosmetic surgery market has witnessed immense growth, with data indicating it will reach up to $50.92 billion by 2028, heavily influenced by media content with associated negative mental-health outcomes.

This normalization of cosmetic procedures continues to extend beyond, with some women seeking out labiaplasty, or breast fillers. In these procedures, the pursuit of physical perfection comes at the expense of sensory experience and sexual pleasure. This is a maddening example of the relentless pursuit of how women are expected to upgrade, mold, and contort themselves to please others’ ever-changing ideals of perfection, akin to Laura Mulvey’s assertion that women exist solely “to be looked at.”

Post-pandemic, the digital matrix is flooded with content relating to plastic surgery and facial enhancements. Paid advertisements endorse a plethora of procedures, from Botox injections to laser hair removal, tailored to one’s local city/area.

Meanwhile, influencers and celebrities flood timelines with seemingly candid breakdowns of their cosmetic journeys, striving to destigmatize the process and normalize the desire for physical perfection. For instance, one immensely followed content creator on TikTok, Alix Earle, has garnered tremendous attention—both praise and criticism–for her “get ready with me” videos. Across various social media platforms, numerous influencers share content similar to Alix Earle's openly discussing their experiences with cosmetic procedures. In some of their most watched videos, they speak openly and enthusiastically about the cosmetic procedures they have undergone and continues to pursue routinely.

On one hand, some view this “transparency" as a positive step forward, applauding the curb away from deceptive beauty standards and the embracement of authenticity. Yet, there’s a significant concern that this openness may simultaneously normalize and even pressure women to resort to invasive alterations at the slight ping of insecurity, rather than taking the time to cultivate self-love and acceptance.

Moreover, this trend of openness or “transparency” seen in media content where women publicly disclose their cosmetic procedures, reflects a societal pressure for women to justify every autonomous choice they make, specifically those regarding their bodies. However, individuals, regardless of gender, should have the freedom to make decisions about their bodies without the need for public validation.

Female public figures, especially those working in beauty or entertainment, often face scrutiny if they don’t openly discuss their alterations, as it perpetuates unrealistic beauty standards for young women. But conversely, if they show signs of natural aging or fail to keep up with trends, they face ridicule and potential career repercussions. This cycle of pressure and criticism creates a lose-lose situation for women, where they cannot escape societal expectations regardless of their choices.

References

Carefoot, H. (2020, March 12). Why beauty brands are removing gender from their marketing. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/hello-coverboy-cosmetics-and-skin-care-brands-turn-to-gender-neutral-packaging/2020/03/02/2c30f49e-54d4-11ea-9e47-59804be1dcfb_story.html

Walker, L. (2022, October 26). Unisex Branding the new normal for skincare. Digital Aesthetics. https://digitalaesthetics.co.uk/news/marketing/skincare-brands-opt-for-unisex-labels

Casey, L., & Casey, L. (2020, February 27). Gender neutral branding – seeing beyond gender | Hatched London. Hatched. https://hatchedlondon.com/gender-neutral-branding-seeing-beyond-gender/

Admin. (2024, March 1). Learn about the best Gender-Neutral marketing examples. The Gender. https://www.thegender.org/learn-about-the-best-gender-neutral-marketing-examples/

Milk Makeup. (2017, March 6). Blur The Lines | Milk Makeup x Very Good Light [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hoTLhHC9ZQw

Mulvey, L. (1985). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In G. Mast & M. Cohen (Eds.), Film theory and criticism: introductory readings (3rd ed., pp. 22–33). New York: Oxford University Press

Zubaviciute, I. (2021, March 30). A gender gap: Why do men still rule the (fashion) world? https://www.notjustalabel.com/editorial/gender-gap-why-do-men-still-rule-fashion-world#:~:text=More%20than%2085%25%20of%20majors,in%20a%20post%2Dpandemic%20world%3F

Media Education Foundation, Jhally, S., & Kilbourne, J. (2010). Killing us softly 4: Advertising's image of women. [Documentary film]. Media Education Foundation.

Sturken, M., Cartwright, L. (2001) ‘Spectatorship, power, and knowledge’, in Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Oxford University Press: Oxford; New York, 72-93, 107-108

Diedrich, J.F.V.K.P.C (2020) ‘Body Image and Global Media’, in The Routledge Handbook of Gender and Communication, Routledge, 146-170,

Menkes, N. (2022). Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power [Film].

Fontinelle, A. (2024, March 27). What is the Pink Tax? impact on women, regulation, and laws. Investopedia.https://www.investopedia.com/pink-tax5095458#:~:text=Researchers%20in%20gender%20inequality%20often,identical%20products%20targeted%20toward%20men.

Senate Rules Committee. "Bill Analysis, California Assembly Bill 1100, Amended 8/31/95," Page 2.

Holt, B. (2021, January 6). The nobody-nose job: how the pandemic led to a rise in plastic surgery. The Guardian. Retrieved May 10, 2024, from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jan/06/plastic-surgery-pandemic-rise

Mulvey, L. (1999). Feminist Film Theory: A Reader. Edinburgh University Press. 10.1515/9781474473224-009

Norman, J. (2021, January 17). Social media normalizes plastic surgery in a dangerous way. The Berkeley Beacon. Retrieved May 10, 2024, from https://berkeleybeacon.com/social-media-normalizes-plastic-surgery-in-a-dangerous-way/

Sloane, J. (2023, October 10). Aging on Screen and on the Page: Changing Depictions of Older People in the Media. Annenberg School for Communication. Retrieved May 10, 2024, from https://www.asc.upenn.edu/news-events/news/aging-screen-and-page-changing-depictions-older-people-media

Wang, Y., Qiao, X., Yang, J., Geng,, J., & Fu, L. (2022, November 2). “I wanna look like the person in that picture”: Linking selfies on social media to cosmetic surgery consideration based on the tripartite influence model. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(2), 252-261. Wiley. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.exlibris.colgate.edu/doi/10.1111/sjop.12882