Fashion Industry Capitalism vs The People

'Skinny Sells'

How the fashion and beauty industry capitalises on insecurity

Body Image and Fashion Over the Years

For the past 100 years, the fashion industry has led public opinion on ideal body image. Throughout this time, we have seen a trend of adhering to abnormal thinness and an onset of disordered eating. The concept of an ideal body has evolved through time but resulting confidence and body image issues, especially in young girls, seem to remain somewhat constant. It is interesting to analyse how these trends have developed and what social results ensued.

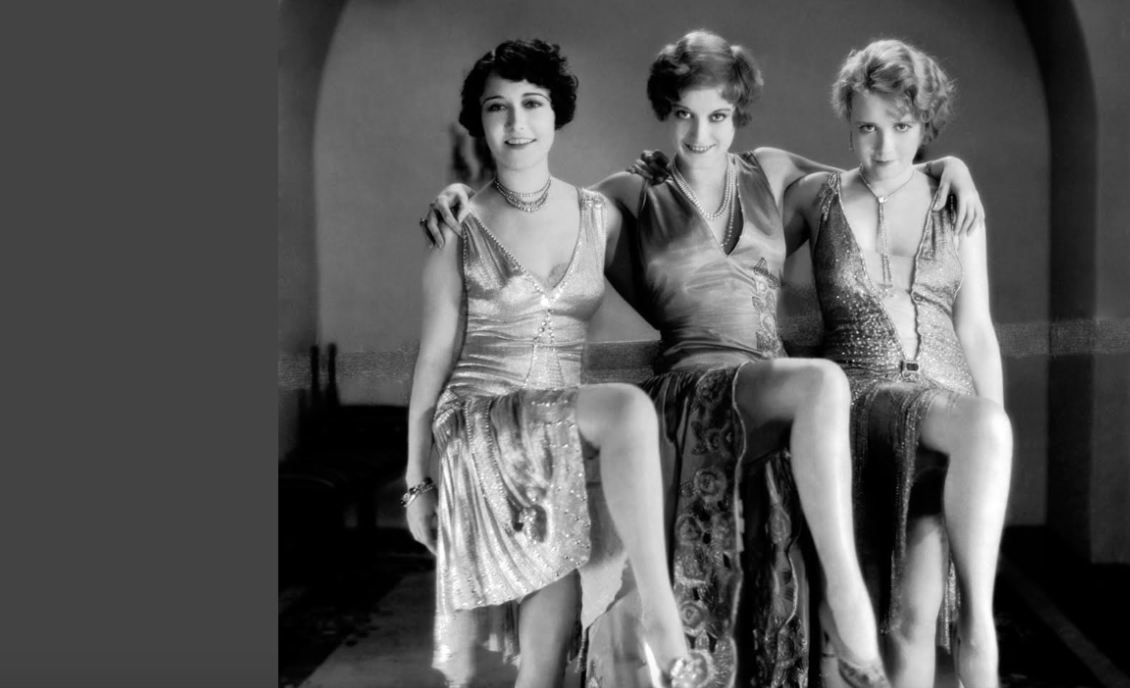

1920's

“the highest reported prevalence of disordered eating occurred during the 1920s and 1980s, the two periods during which the ‘ideal woman’ was thinnest in US history”

This timeline commences 100 years ago in the 1920s. With the post-war climate of the 20s came the rise of the flapper girl. These women broke away from the social norms of the Victorian Era by wearing shorter skirts (which was considered knee length at this time), cutting their hair short and veering away from the boundaries of only marital sex (Rosenberg, 2020). This was consistent with a small aspect of first wave feminism. First-wave feminism had a fairly simple goal: have society recognise that women are humans, not property (Soken-Huberty, 2022). The rise of the 1920s flapper reflected this shift toward the Western world desiring a more slim physique (Howard, 2018). Although women were intending to increase their freedoms, they also were forging a basis for the male gaze to burgeon and flourish. The rise of hemlines and the growth of sexual promiscuity abetted the idea that one's attractiveness corresponded with one’s sexual prowess. The ideal body type at this time was very thin and so sparked an eating disorder epidemic among young girls. According to a study in the journal of communication (Kantor and Harrison, 2006), “the highest reported prevalence of disordered eating occurred during the 1920s and 1980s, the two periods during which the ‘ideal woman’ was thinnest in US history”.

1960s - 1970s

"In order for your body to be truly fashionable, you had to probably change it in some way"

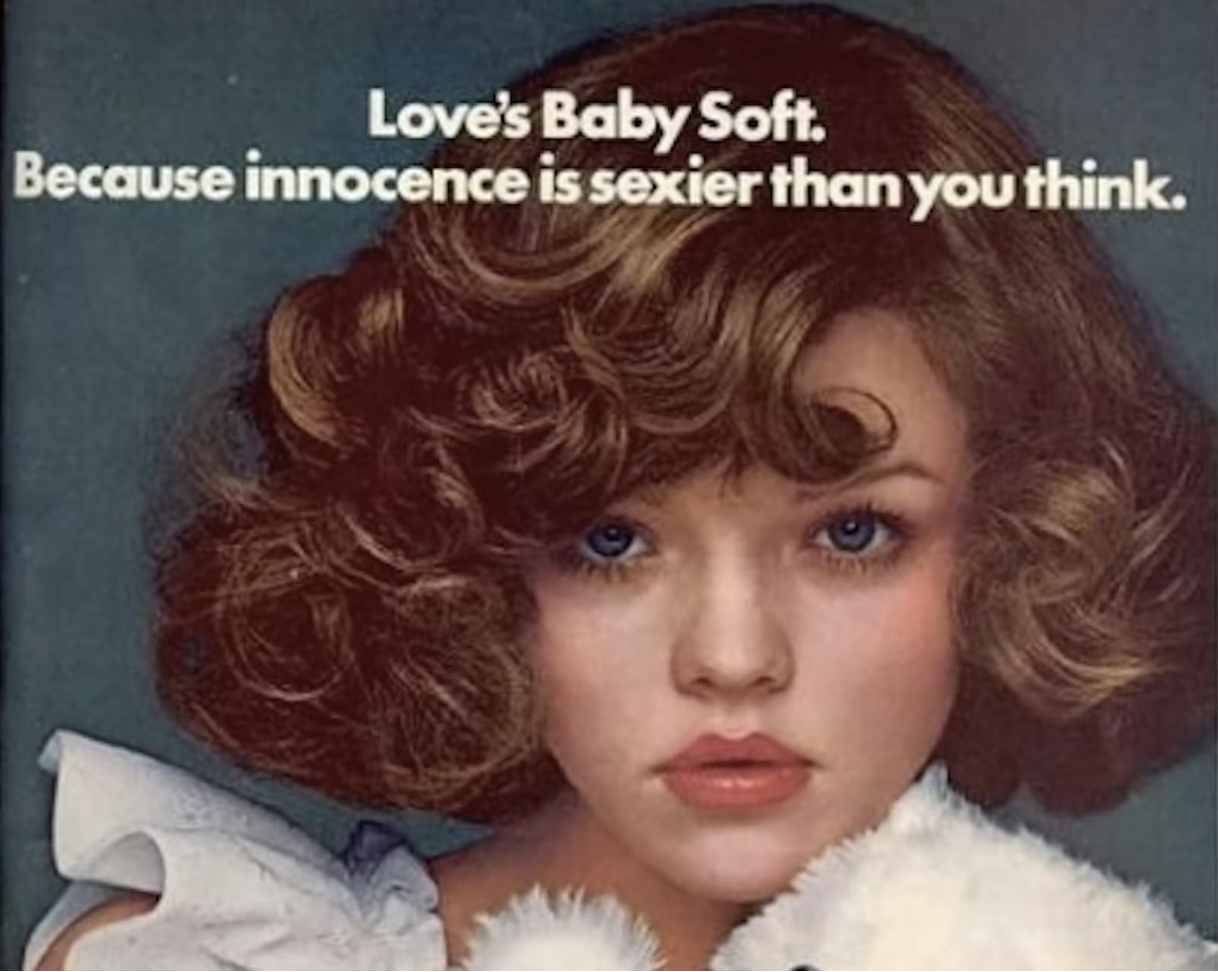

Until the 1960s, shape-wear was marketed as the most efficient way to achieve the idealised physique. Although conscious eating had always been coaxed to some extent, at the turn of the 1960s it was promoted much more. Corsets were hence replaced by diets and exercise (Howard, 2018). And although there was this general belief that women had been freed from the confines of corsets, societal pressure to adhere to these unrealistically small body types still remained. Ultra thin models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton rose to fame in this period, reinforcing that looking super thin and very young were desirable traits. Emma McClendon, the Fashion Institute of Technology’s associate curator of costume notes that what remained of womens’ confinement was the “notion that in order for your body to be truly fashionable, you had to probably change it some way” (Howard, 2018).

1980s - 1990s

In the late 80s, the popularity of thinness remained, however, a more athletic and healthier look came about exemplified in forms such as of Cindy Crawford, Kim Alexis and Demi Moore. With this decade also came the introduction of the concept of supermodels. The healthy ideal did not last long as the ‘heroin chic’ look came into popularity. Burgeoned by the waif figures of the likes of Kate Moss, popular commercials and advertisements favoured women who looked malnourished and vulnerable. The media glamorised unhealthy body types and behaviours. This was criticised heavily by many, including president Bill Clinton (Helmore, 2020). Ironically, around that same time, the World Health Organisation began sounding the alarm about the growing global obesity epidemic (WHO, 2022). As various images denouncing obesity flashed across media screens as a part of public health outreach efforts, so did images of stick-thin models. Hence igniting the war on obesity. Larger body types in this time period were now labelled as unhealthy and being overweight became a public enemy. Despite that the measures used to attain ultra-thinness in many cases were likewise damaging, to be overweight was seen as a manifestation of laziness and unhealthiness, whereas to be slender was believed to epitomise health. Very little was done to combat the eating disorder epidemic that accompanied the obesity epidemic. This truly illustrated society’s reverence for being ‘skinny’ and phobia of being considered ‘fat’.

The 2000s

Coming into the 2000s, the thinness epidemic reached demographics younger than ever before as an effect of globalisation and easier access to mainstream media. Nearly a third of children aged 5 to 6 in the US select an ideal body size that is thinner than their current perceived size when given the option, and by age 7, one in four children has engaged in some kind of dieting behaviour, according to a Common Sense Media report published in 2015 (Howard, 2018). A large contributor to this negative influence on body image from a young age was the media. Magazines at this time were one of the biggest instigators of these toxic mentalities. Women and mens' bodies were constantly scrutinised under the public eye and publicising an image without photoshop was considered career ending (unless it was a criticism). Widespread acceptances of these detrimental mindsets could also be seen in most media sources such as tv, film and advertising. The term 'guilt-free' was coined in advertising to suggest that consumers should feel guilty consuming any sort of product that contained calories. Many magazine publishings promoted fad diets, exercise routines and even diet pills.

The toxic diet culture & fatphobia of early 2000's chick flicks

80's Calvin Klein Ads

Featuring the thin 17 year old Kate Moss with 22 year old Mark Wahlberg. Moss is made to seem young and vulnerable while Mark is portrayed as strong and mean.

2000's Magazine Body Shaming

Shaming celebrities, both male and female, for everything from wrinkles to cellulite.

The Ideal Model

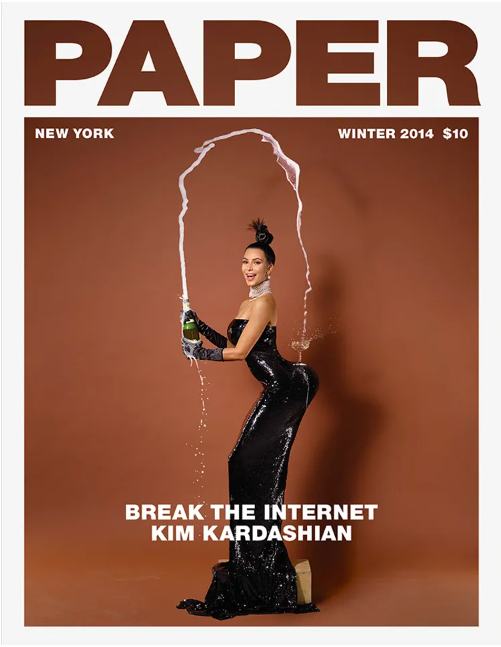

The ideal model today still resembles those of times past. With the popularisation of the Kardashians also came the popularisation of the hourglass figure. The ideal body shape, according to popular media, is to have larger breasts and wider hips, while maintaining a thin, toned torso and slim legs – a body shape that is uncommon in natural occurrences. The beauty standard commonly accepted in society is a very westernised version of beauty. Those of different cultures are often idolised when they conform to western beauty ideals.

An example of this is Aishwayra Rai who won Miss World in 1994 for India and was called ‘the most beautiful woman in the world’ by actress Julia Roberts (Osuri, 2008). She was worshipped internationally for being a great Indian beauty, however, many of her features are very western: her lighter complexion, her blue eyes and her facial structure. This exemplifies that standards of whiteness often govern gendered notions of beauty (Osuri, 2008). In certain asian countries, this admiration of caucasian traits has popularised skin-whitening products, eye widening products and many more products that help women reach the idolised western look. The inclusion of foreign and diverse models in fashion, advertising and film has risen in popularity as the world pushes for greater representation and diversity in the media. Yet the majority of what is still seen and revered is white mixed-race, white passing or westernised ideals of beauty. Another major downfall of the current beauty standard is the fetishisation of the young and the condemnation of growing old. This creates a toxic mindset for women that their value as a person decreases with age.

In general, the constant reiteration of the importance of fashion and beauty in the media devalues women as people and subjects them to mere objects for others' appreciation. The unattainability of these beauty standards is utilised to perpetuate insecurity and breed a society obsessed with self-improvement and consumption. The fashion and beauty industries capitalise on the pressure women feel to stay looking young, thin and beautiful.

Young Aishwarya Rai

Expansions Of The

Beauty Standard

Although the beauty standards of today continue to reflect the harsh standards of the past, there have been signs of improvement. This is demonstrated by the increase of plus-sized models in advertising, a greater use of older models and in the expansion of racial diversity (not just in a white-washed sense). Brands such as fenty are leading the crowds with their all inclusive make-up and fashion line that uses models of all shapes, colours and ethnicities. Public consciousness of these detrimental mindsets has also increased. Television, film, advertisements and all sorts of media are becoming more conscious and inclusive as the demand for inclusivity grows. The broader representation of gender, ethnicity, age and beauty has seen a greater acceptance towards different types of beauty, somewhat challenging the standard. Victoria's Secret presents a popular example of the times changing as their notorious yearly fashion shows were cancelled after 24 years due to the harsh standards they held for their models. Despite these steps in the right direction, eating disorders are still on the rise worldwide (Graber, 2022) and the fashion and beauty industry is as successful as ever (Roberts 2022).

This illustrates that the preexisting prejudice towards weight gain and unattractiveness in society is an issue that will take teaching younger generations and mindset changes over many years to improve the negative mindsets society has taught women to have about their bodies.

Female Sexualisation, Exposure and Influence:

Internet celebrities vs traditional celebrities

In the terms of media content, the sexualisation of women in media is women over-emphasising their body parts, and their sexual willingness, either posted by companies or themselves on their media platforms. YouTube and Instagram celebrities or ‘influencers’ are able to influence trends in fashion, beauty and behaviour in society to greater extents than traditional celebrities.

Internet celebrities expose ordinary women to unrealistic beauty standards.

Kim Kardashian, a very familiar name.

The extremely well-known celebrity who has 328 million followers on the social media site Instagram. Kim Kardashian is known as the American television personality on ‘keeping up with the Kardashians, an entrepreneur for her company ‘SKIMS’ a fashion line creating shape-wear, loungewear, and underwear. However, Kim Kardashian's platform can be harmful to females, due to the unrealistic curvy body she has.

Kim Kardashian is well-known for revealing herself to the public, from her own media platforms, her brands, and the use of her body in magazines and other types of media. The world of media exposes women to incorrect messages about the stereotypical and unrealistic body types, that over-sexualised women's body parts. This influence of toxic body image stereotypes is the main catalyst for body issues for women that are not involved in the media. Every day women see magazine articles, billboards and social media posts and feel less satisfied with their bodies because of how someone else's body looks. This is due to surgeries, makeup and editing skills, which are seen as the constructed version of the ideal body type that society wants, not a version that is realistic.

Her shapewear brand has a waist trainer. This piece comes in at $135NZD, which Kardashian wears herself, as it ‘just makes me feel really snatched’ and she does looked snatched. However, she has an iconic curvy body, which is very unrealistic. Consumers of the skims brand need to realise that they cannot expect the skims products to have the same effect on themselves, then they do with Kim Kardashian herself.

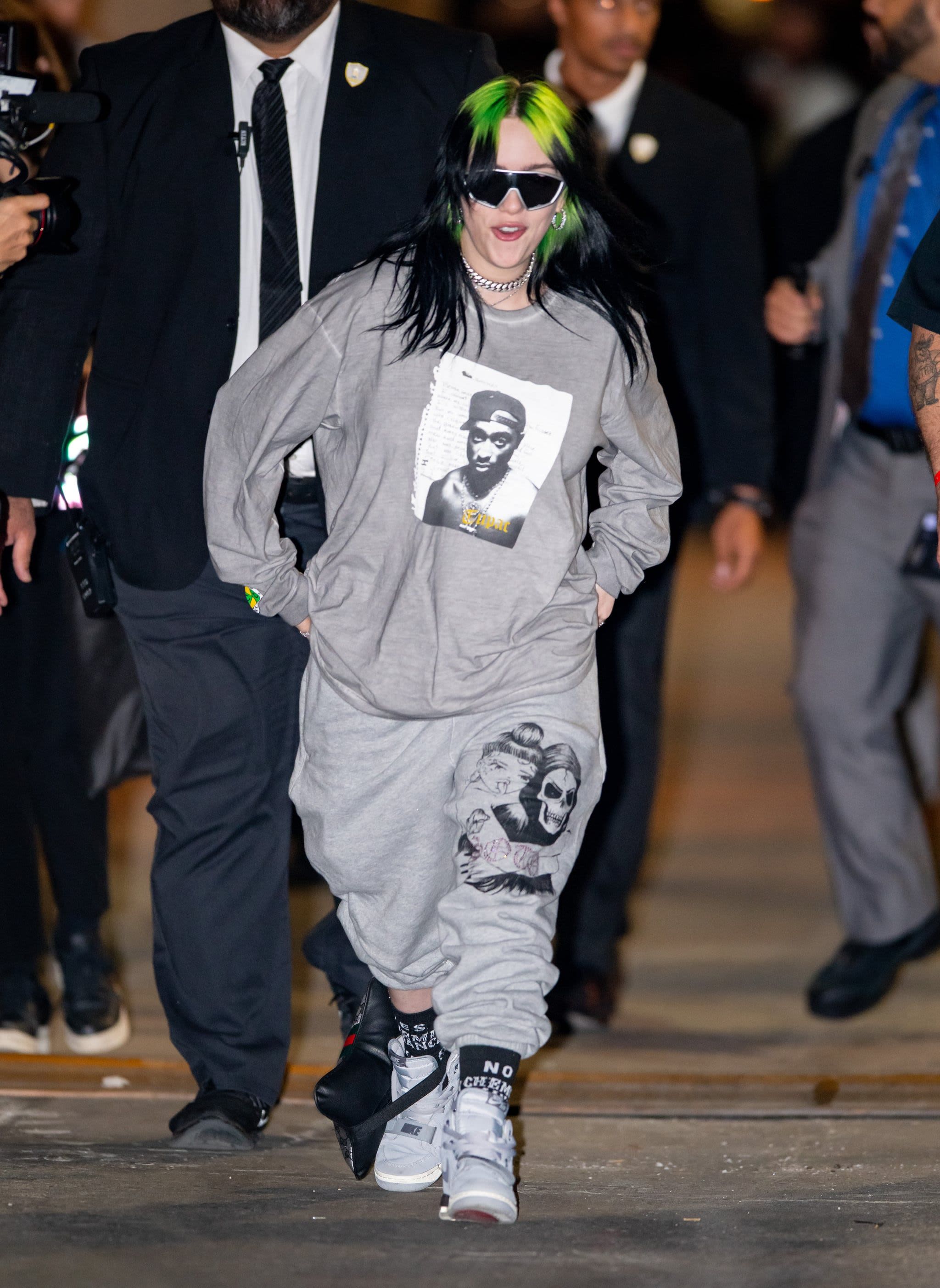

Billie Eilish is an American singer and songwriter. A lot of media about Eilish is strictly focused on her body, and especially what was under the baggy clothes she has been wearing since the age of 14. In 2019 Eilish stated in a Calvin Klein ad "I never want the world to know everything about me," she says. "I mean, that’s why I wear big, baggy clothes. Nobody can have an opinion because they haven’t seen what’s underneath, you know?". As Eilish was so young when she was introduced to the world, it was important for her that the media and the world focused on the music she was creating, and the topic was not restricted to her body image, and being over-sexualised while she was a teenager.

Even though Eilish’s body is so publicised, due to her rising fame and success, she embraces the attention and uses it to educate and send messages to others about the toxicity of the media and the media’s response to celebrities and their bodies. This response to the media’s publicity is positive, in regards to ensuring she was not going to become famous for the body she had, but instead for the talent she had and how she could connect with people and her fans through her music.

"Suddenly you're a hypocrite if you want to show your skin, and you're easy and you're a slut and you're a whore," – "If I am, then I'm proud. Me and all the girls are hoes, and fuck it, y'know?"

Performing Women

The Gaze

The use of media to determine the way that society looks at bodies creates a patriarchal feminine body, the ideal women's body for men. The idea of the gaze was originally developed by Michael Foucault when looking into the surveillance of bodies. The surveillance of bodies can be best described as a metaphorical gaze. Not only is the gaze an in-person act, but it is also surveillance that is utilised on all forms of media that allow ordinary women to compare themselves to beautiful women.

The Male Gaze

The male gaze was thought of by Laura Mulvey in 1973. The Male Gaze takes the thoughts of Michael Foucault and makes a feminist opinion on it. The male Gaze highlights the perspective of typical straight males, and how this perspective is on women. This perspective views women as sexual objects and is viewed for man's pleasure. Although the term male gaze is used as a film theory, it is appropriate in also looking at the patriarchal structure in everyday society.

.

The Internalised Male Gaze - 'Performing Women'

"The moment I realised I wasn’t just living for myself but for some imagined male audience I had mustered up in my head, I was horrified and honestly, ashamed"

The internalised male gaze can be referred to as women unconsciously ‘performing’ to a standard for an audience, a male audience. From a young age, girls are taught that approval from men is important for their own satisfaction, not only is this an unconscious trait happening in daily life, but it is a trait that has been taken onto social media and the way we use it. Social media site Instagram is the perfect example, originally formed for individuals to share experiences with friends, now used as individuals platforms to edit photos, posted at the ideal time to gain a good amount of interaction.

Women are constantly objectifying their own appearances, and their actions, from the perspective of a male audience. However, this audience is non-existent. It is an unconscious desire for attention from males. It is how the patriarchal structure of society exploits women and makes women feel insecure.

"Every aspect of my daily life from what I ate, how I dressed, the personality I presented (always the “cool girl”), the hobbies I had, the songs I listened to, and the media I consumed; were all subconscious decisions that I believed would best align with and please these “powerful all-seeing men”.

Advertising and the Male Gaze- Hyper-sexualisation of Femininity

A common theme in advertisements over the years tends to sexualise women and show them in a passive, submissive way. This contrasts with how men are perceived, which is a masculine, dominant way. When ordinary women observe other women performing for the male gaze in advertisements, they are unconsciously attracted to the products or clothing they are advertising. This can be referred to as women internalising the male gaze, and acting as a performing woman, for the satisfaction of the male audience.

Comparing society’s ideal body type to themselves creates a belief that individuals should see them in similar ways that they perceive the patriarchal feminine ideals, that the media loves to give attention to. In relation to internet celebrities and the products that they influence non-famous women to buy, the same ideology can be used. Internet celebrities expose ordinary women to unrealistic beauty standards.

The Gender Ads Project Site is an educational resource. The main focus is on the ways in which gender and related issues like sexuality, social class and race, intersect with advertising.

Capitalism and The Fashion Industry

Capitalism and the Fashion Industry

At its core, capitalism is an economic system which uses money to make more money.

As described by Britannica: “Modern capitalist systems usually include a market-oriented economy, in which the production and pricing of goods, as well as the income of individuals, are dictated to a greater extent by market forces resulting from interactions between private businesses and individuals than by central planning undertaken by a government or local institution. Capitalism is built on the concepts of private property, profit motive, and market competition.”

To summarise, it is essentially a decentralised powerhouse of production and consumption, and it shapes and dictates our modern western societies directly, with its effects being seen everywhere including in the fashion industry. Fashion is a great example of capitalism in motion, with new trends cropping up weekly, mass consumerism of quantity over quality and a heavy focus on a buyable look...

The production/ consumption duality propels our consumeristic society forward, and shapes the framework which dictates our identities as consumers. Women, considered the most powerful consumers and influencers, are the fastest-growing market in the world, especially fashion (Barletta 2006) - Making them targets in many ways.

Women and the fashion industry

The way the fashion industry preys on women is incredibly expansive and deep rooted, from the way the female body and women are treated by the industry, to the way it manipulates the wants and needs of women for capital gain.

A documented example (Cwynar-Horta, 2016) is the politicisation and commodification of the Body Positive movement by corporations. As Instagram for example, turned into an advertising platform in 2013, the commercialisation of user activity became essential to advertisement. Under this umbrella of commercialisation, the body positivity movement was also targeted and exploited in order to successfully reach more users to advertise to. This process is an example of the way in which a movement by women for women was simply just absorbed and used by the capitalist system for its benefit, taking power away from the narrative of the movement and women alike in the process.

This narrative of use for profit can also be observed at a higher level; in an article on bodily capital Mears (2015) notes the use of male appropriation of the female body as a symbolic resource to “generate profit, status, and social ties in an exclusive world of businessmen”. She argues that women are unable to capitalise on their own body due to the structures in place, both in the business and socially. It is easy to observe the way in which this observation is replicated over and over, with women’s bodies selling products on behalf of men. A good example being Bernard Arnault, a businessman who owns the luxury conglomerate LMVH which includes Christian Dior, Fendi, Givenchy and many more. A study conducted by Oniku and Joaquim (2021) found that female sexuality is strategically used to influence buying behaviours of youth in Nigeria, a finding that can almost certainly be applied to the fashion industry worldwide.

An article by i-D magazine reported on the ways in which the fashion industry effects young women’s bodies. It talks about the relationship between eating disorders and issues with body image of women with the capital gain and growth of the industry. The quote; “Together with the media and fashion industry, the powerful diet food industry has artificially created a ‘problem’ which has resulted in the vast majority of women in Britain and other western developed countries thinking that they need to diet”. It talks about the power of advertising, fashion stores and beauty pages in undoing the fight against this conformist body image and its effects. This article is worth reading, a link is attached.

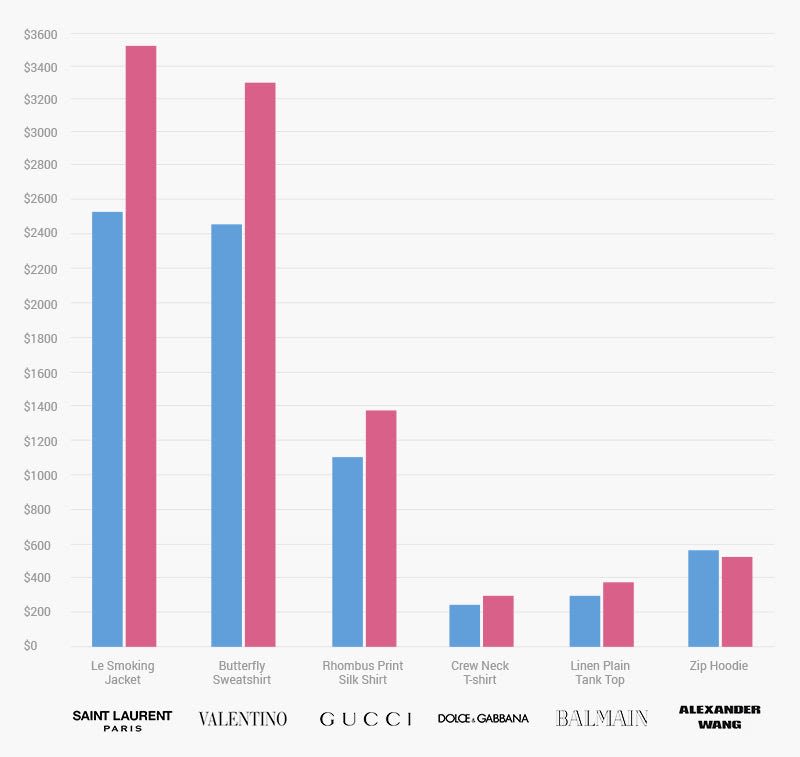

If using women’s bodies for profit and capital gain wasn’t enough, the use of women consumers is also abused. The famously dubbed ‘pink tax’ persists in society today and continues to contribute to gendered price disparity. Pink tax refers to a phenomenon in which women consumers pay an additional price for products and services that are similar and equivalent to those of men, particularly when products are targeted toward women (Khemka, 2021). While it is most visible in hygiene and self-care products, it is very present within the fashion industry too. Khemka's (2021) article on the pink tax and how to combat it is also attached below.

The Public Effect

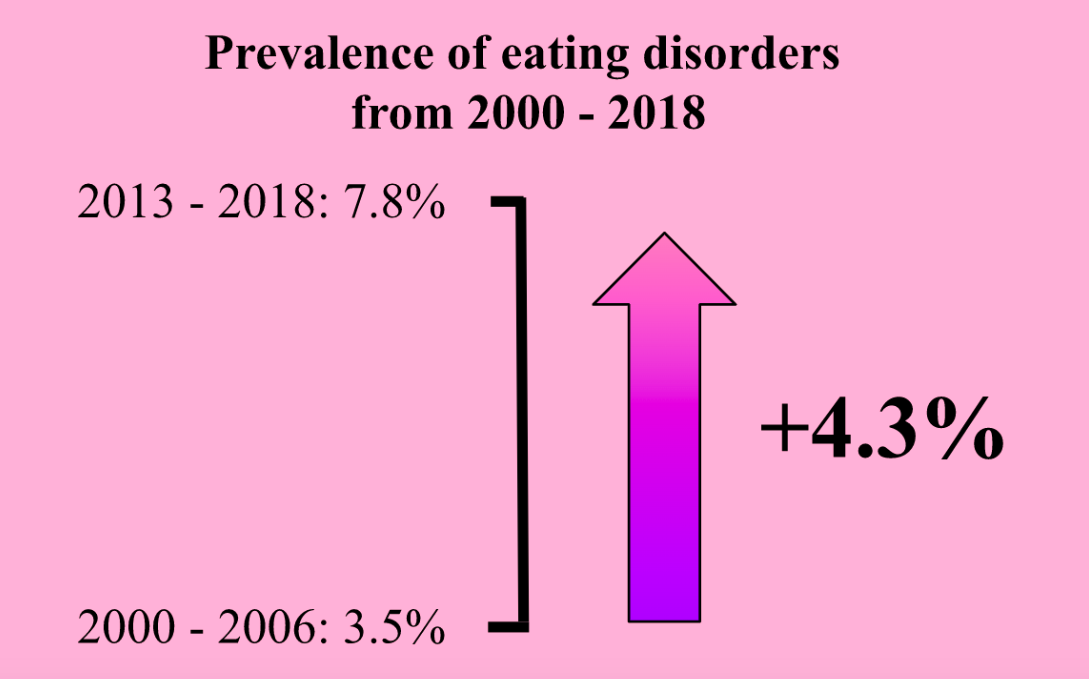

The prevalence of eating disorders has increased by 4.3%, a double in proportion since 2000-2006.

Researchers at the national eating disorder association (US) have discovered a link between the use of Instagram and increased self objectification and body image concerns.

Those working in the fashion industry are especially affected. Vogue interviews 9 models on the pressure to meet the extremely harsh standards of the industry and our media.

Exposure to thin models has been found to deteriorate body image while increasing body dissatisfaction and anxiety. Conversely, exposure to overweight models has been found to improve body image and decrease body dissatisfaction (Moreno-Domínguez et al., 2018).

Conclusion

It is clear that the fashion industry has come a long way but it still has a long way to go in terms of improving mindsets towards body image and adequacy. The increase in diversity of models and representation of different shapes, colours and sizes has had a positive effect on the population but trends still suggest that there is a problem at large. With the introduction of social media came more access to sites for comparison and these unrealistic ideals for beauty are now being seen in 'regular people'. Much of what is popularised in our advertising and media conforms to the concept of the male gaze. Sex appeal is used to promote products and is used in the general media very frequently. People then correspond their self worth with how attractive and sexy they are. All of the harsh standards work to maintain a capitalistic society obsessed with consuming. If the media can convince consumers they are imperfect, they can capitalise off of their insecurities.

Presentation by

Juliana Rossi Macaes

Jody Burrell

Emese McIntosh

References

Alson, T. (2021, July 14). Billie Eilish: ‘People Are Scared of Big Boobs’. Paper Magazine. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://www.papermag.com/billie-eilish-instagram-followers-2655085819.html?rebelltitem=1#rebelltitem1

Boettke, P. J. (2019). Capitalism. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/capitalism

Cwynar-Horta, J. (2016). The Commodification of the Body Positive Movement on Instagram. Stream: Culture/Politics/Technology, 8(2), 36–56. file:///Users/emesemcintosh/Downloads/203-Article%20Text-802-2-10-20161231.pdf

Duncan, M. C. (1994, February). THE POLITICS OF WOMEN’S BODY IMAGES AND PRACTICES: FOUCAULT, THE PANOPTICON, AND SHAPE MAGAZINE. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 18(1), 48–65. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1177/019372394018001004

Graber, E. (2022, January 13). Eating Disorders Are on the Rise. American Society for Nutrition. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://nutrition.org/eating-disorders-are-on-the-rise/#:%7E:text=Published%20April%202019%20in%20The,rise%20in%20eating%20disorders%20worldwide.

Harrison, K., & Kantor, J. (2006, February 7). The Relationship Between Media Consumption and Eating Disorders. Journal of Communication, 47(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1997.tb02692.x

Helmore, E. (2020, March 26). 'Heroin chic’ and the tangled legacy of photographer Davide Sorrenti. The Guardian. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2019/may/23/heroin-chic-and-the-tangled-legacy-of-photographer-davide-sorrenti

Hershkovits, D. (2014). How Kim Kardashian broke the internet with her butt. The Guardian, 17. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/dec/17/kim-kardashian-butt-break-the-internet-paper-magazine

Howard, J. (2018, March 9). The history of the ‘ideal’ woman and where that has left us. CNN Health. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://edition.cnn.com/2018/03/07/health/body-image-history-of-beauty-explainer-intl/index.html

Khemka, S. (2021, September 11). Pink Tax: How Women are paying more for Fashion. Fashion Law Journal. https://fashionlawjournal.com/pink-tax-how-women-are-paying-more-for-fashion/

Kok, J.A. (2020). The Performer Identity Of Billie Eilish-And Why It Constructs The Concepts Of Performance, Authenticity & Liveness (Bachelor's thesis). Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://studenttheses.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12932/36029/BA%20Eindwerkstuk_Scriptie_Jeroen%20Kok_Definitief.pdf?sequence=1

Lafferty, M. (2019). The Pink Tax: The Persistence of Gender Price Disparity. Midwest Journal of Undergraduate Research, 11, 56–72. MJUR. http://research.monm.edu/mjur/files/2020/02/MJUR-i12-2019-Conference-4-Lafferty.pdf

Magnolia Creek. (2019, May 23). Social Media’s Impact on Eating Disorders. Retrieved September 19, 2022, from https://www.magnoliacreek.com/resources/blog/social-media-and-eating-disorders/

McWhorter, L. (1999). Bodies and pleasures: Foucault and the politics of sexual normalization. Indiana University Press. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1090&context=bookshelf

Mears, A. (2015). Girls as elite distinction: The appropriation of bodily capital. Poetics, 53, 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2015.08.004

Moreno-Domínguez, S., Servián-Franco, F., Reyes del Paso, G. A., & Cepeda-Benito, A. (2018, August 11). Images of Thin and Plus-Size Models Produce Opposite Effects on Women’s Body Image, Body Dissatisfaction, and Anxiety. Sex Roles, 80(9–10), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0951-3

Nouri, M. (2018). The power of influence: Traditional celebrity vs social media influencer. Santa Clara University Scholar Commons. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=engl_176

Oniku, A., & Joaquim, A. F. (2021). Female sexuality in marketing communication and effects on the millennial buying decisions in fashion industry in Nigeria. Rajagiri Management Journal, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/ramj-09-2020-0055

Osuri, G. (2008, October). Ash‐coloured whiteness: The transfiguration of Aishwarya Rai. South Asian Popular Culture, 6(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14746680802365212

Roberts, R. (2022, June 25). 2022 Beauty Industry Trends & Cosmetics Marketing: Statistics and Strategies for Your Ecommerce Growth. Common Thread Collective. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://commonthreadco.com/blogs/coachs-corner/beauty-industry-cosmetics-marketing-ecommerce#:%7E:text=Globally%2C%20the%20industry%20is%20strong,And%20%24784.6B%20by%202027.

Rosenberg, J. (2020, March 25). Flappers in the Roaring Twenties. ThoughtCo. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.thoughtco.com/flappers-in-the-roaring-twenties-1779240

Smink, F. R. E., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012, May 27). Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 406–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

Soken-Huberty, E. (2022, April 24). Types of Feminism: The Four Waves. Human Rights Careers. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.humanrightscareers.com/issues/types-of-feminism-the-four-waves/#:%7E:text=Three%20main%20types%20of%20feminism,liberal%2C%20radical%2C%20and%20cultural.

Sparhawk, J.M. (2003). Body image and the media: the media's influence on body image. The Graduate College, University of Wisconsin. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/41081/2003sparhawkj.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Team. (2014). how the fashion industry affects the bodies of young women. I-D.vice.com. https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/9kybkv/how-the-fashion-industry-affects-the-bodies-of-young-women

WHO. (2022). Controlling the global obesity epidemic. World Health Organisation. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.who.int/activities/controlling-the-global-obesity-epidemic